This post does not contain spoilers for BoJack Horseman Season 4.

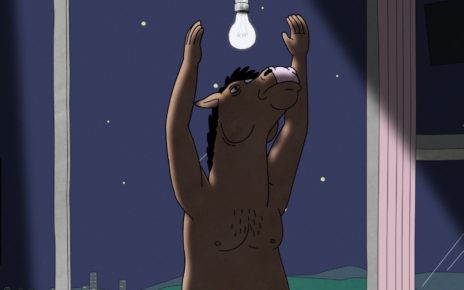

For some people, BoJack Horseman comes off as pure parody: the melodrama of the washed-up celebrity, numbed with booze and narcotics and insatiable in his appetite for meaningless sex and muffins, hooked on the shame and regret as much as on the vices themselves. But for some of us, BoJack, which just debuted its fourth season, is not a caricature but a mirror, and the show is closer to prestige television than it is to Saturday morning animation. For all the tongue-in-cheek sitcom plotlines — and, yes, the fact that most of the main characters are animals, not people — the way BoJack portrays trauma, addiction, and depression is exceptionally human.

Anyone with a pulse and a period of depression behind them will recognize BoJack’s vices as flailing attempts to feel something. (“Nothing on the outside, nothing on the inside.”) This is well-trod territory for prestige TV — think Don Draper’s whiskey and women or the cocktail of opiates that feed Elliot’s dissociative identity disorder in Mr. Robot.

But there’s another layer to BoJack’s self-medicating that I’ve rarely seen expressed so clearly on television. It’s something trickier to capture, and harder still to expect an audience to recognize and empathize with: he’s not just unable but unwilling to let go of his vices, even as he recognizes their catastrophic effects on his own life and the lives of the people who care about him. He’s come to define himself by them. “It doesn’t get better and it doesn’t get easier,” he admits to Diane in season three. “I can’t keep lying to myself, saying that I’m going to change. I’m poison.” That’s a pernicious consequence of mental illness. The illness itself becomes your identity. The more rooted it becomes, the more the poison spreads.

“I have poison inside me, and I destroy everything I touch.”

There’s a large body of psychological literature that focuses on how childhood trauma, abuse, and neglect can result in a pathological need to feel special, and neuroscience research suggests that trauma can prime the brain for substance abuse and personality disorders later in life. For BoJack, the need to be “special” was implanted in him outright. “You’ve got to give the people what they want, even if it kills you — even if it empties you out until there’s nothing left to empty,” Beatrice Horseman tells her son as a colt.

We don’t talk about this very often (outside of the arts, of course), but there’s a certain romanticism inherent in being fucked up that has been baked into our culture over time. Depression and addiction have become shorthand for deep, interesting, worthy of attention. It’s what Sad Girl Twitter is built on. It’s why Cat Marnell has a book deal. We “fetishize [our] own sadness,” to quote BoJack’s one-time publicist and lover. We lyricize our brokenness and give it a poetic sheen. “I have poison inside me, and I destroy everything I touch,” BoJack tells Diane. After a while, you don’t know how not to be damaged, and you forget why you’d ever want to be whole. It feels profound to hurt so deeply.

Yet BoJack is in a position of privilege that only celebrities (and maybe teens on Tumblr) can enjoy. He has the luxury, such as it is, of being able to simultaneously revile and be rewarded for his addictions. Diane’s memoir reveals to the world what a profoundly broken creature BoJack is — and he quickly finds out just how lucrative being a broken creature can be. His career gets a jump start. The women he sleeps with are more attentive. It’s awfully hard to give up a vice when it’s making you money and getting you laid.

The show acknowledges these contradictions without necessarily ascribing a value judgment to them. It even implies that BoJack may not be able to sustain a career without this pathologized identity.

As season two opens, he’s landed his dream role in Secretariat and is listening to self-help audiobooks narrated by George Takei in a hapless grasp at happiness. It makes him a terrible actor. Then Beatrice calls. “You were born broken. That’s your birthright,” she tells him. “You can fill your life with projects, your books and your movies and your little girlfriends, but it won’t make you whole. You’re BoJack Horseman. There’s no cure for that.” He returns to set and delivers his line, pained and resigned. It takes this grim pep talk to draw out his hidden depths.

If getting healthy means admitting that you’re not any more special, or any more fucked up, than anyone else, well, that’s a bitter pill to swallow. After all, the dreams of “special” people are what keeps Hollywoo afloat.

But the show also reminds us that there’s a limit to the sympathy of others. As friends and lovers break away, BoJack (maybe?) comes to see that he can only wallow without consequences for so long. “You can’t keep doing shitty things and then feel bad about yourself like that makes it okay. You need to be better,” says Todd — sweet, long-suffering Todd. “You are all the things that are wrong with you.”

After a while, BoJack Horseman reminds us, you are your misery. There’s no easy cure for that.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to ❤ this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.