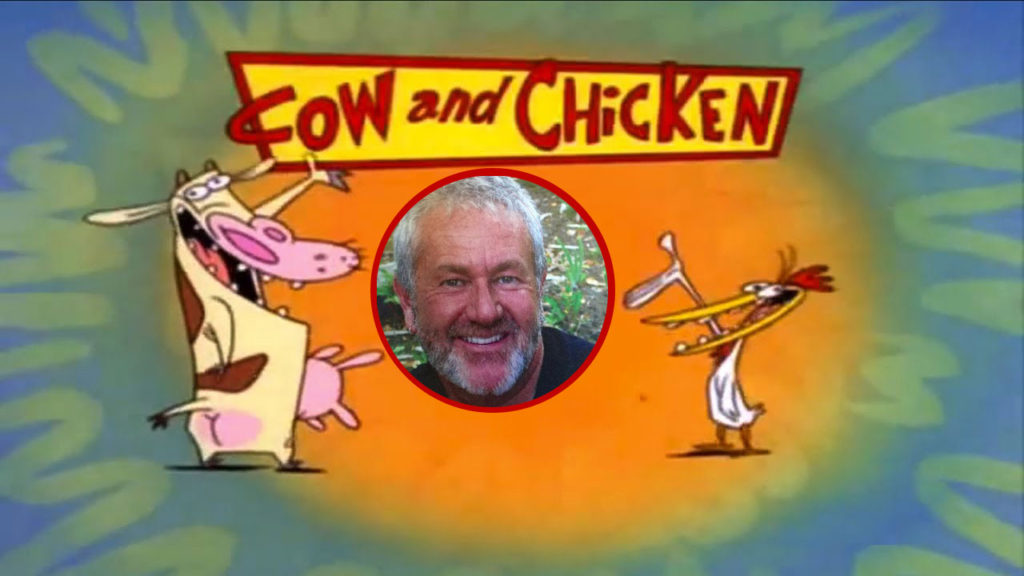

Charlie Adler is one of the most prolific voice actors not only of his generation but of all time. The voice behind T-Bone in SWAT Kats: The Radical Squadron, Buster Bunny in Tiny Toon Adventures, Ed and Bev Bighead in Rocko’s Modern Life, and Ickis in Aaahh!!! Real Monsters shaped a generation of characters in the 1990s, and still works regularly today. And in Cow and Chicken and I Am Weasel, two Cartoon Network shows created by Dave Feiss that came out of Hanna-Barbera’s What a Cartoon! program, he was…well, pretty much everyone—Cow and Chicken, their loony nemesis the Red Guy, and I.M. Weasel’s dim-witted foil I.R. Baboon.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of What a Cartoon!, Adler joined The Dot and Line to discuss how he found his voices, what working with Star Trek‘s Michael Dorn—who voiced Weasel—was like, and what it meant to be involved with cartoons at a time of boundless creativity.

How he got the jobs…

I warm up to do my job and I warmed down by singing. And what was in my tape deck at the time was, Little Shop of Horrors. Ellen Green was just in my head, singing “a matchbox of our own.” I would always sing the different voices in the shows. So I auditioned for Cow with that voice, because it just tickled me, and the green room laughed, they responded to it. Chicken was just me in my teen years, what I sounded like then. I was too embarrassed to keep my Bostonian accent, which is where I learned to talk when I was a kid, so when I moved to New York at six I started to talk like I was from Brooklyn so they wouldn’t beat the shit out of me. So that was Chicken. And then the Red Guy, I loved the drawing, and the absurdity of all of it. I have no idea where that voice came from, but it made me laugh. And I’ll be a son of a bitch, but I got all three. At the time, Cartoon Network didn’t want anybody doing more than one voice. They felt somehow that they were going to held up for money or whatever those production people worry about. But Dave absolutely insisted.

How he met Michael Dorn, the actor behind Star Trek‘s Worf, who played Weasel…

Michael Dorn is a very dear lifelong friend as a result of I Am Weasel. Very early on, Michael came in and met me, and I don’t know if you know how I work, but I’m kind of nuts. I’m just swinging from the walls, free-falling, having a great time. We never saw the scripts ahead of time. We just hit record rent. So everything was a frantic, insane cold read. There weren’t rehearsals. And Michael was very formal. I mean, very formal. And I’m just wanting to dance with him, and he’s just not having it. And about 15 minutes into this, I looked at him—as he has told often, wherever he can be heard—and I said, “Who the hell are you, Olivia de Havilland? Lighten up!” I might’ve said Joan Fontaine. Because when we see each other—they were sisters—I call him Joan and he calls me Olivia. So I said, “Who the hell are you, Joan Fontaine?” That’s what it was. And his eyes got so wide, and then he just started to laugh, and it was just instant friendship.

On chemistry in the recording booth…

If there’s no chemistry, if there’s no joy together, if there’s no relationship, there’s no nothing—that’s in the theater, that’s in television, that’s in anything. And we just fed off of each other. It was absolute bliss, that show. And we had the most thrilling co-stars. One day we had Dom Deluise and and Ed McMahon at the same time, and we were all crying. Weirdly, Dom’s wife, Carol Arthur, a wonderful actor, went to high school with my father. It’s so weird, all these life connections you make. But I remember sitting in that room with Dom, and Dom was falling over laughing at us being such fools.

On scripted dialogue versus improv…

David was never heavy-handed. The writers were never heavy-handed about any of it. They were not precious about it. They had great writers—Steve Marmel, Michael Ryan, who’s so prolific, and David, and freelance writers who were utterly brilliant. Nobody went, “Oh, no, no, no, no. You can’t possibly say that.” We’d hear them laugh. We’d see it. They were so well written. We may have augmented stuff if something didn’t feel exactly right in terms of phrasing things. They were open to what we had to bring, and it was so well done from their end of the collaboration that I don’t think any of us really needed to noodle with it. We would riff on each other, you know, things would happen spontaneously, and they would keep it. That was the spirit of the entire 3,000,075 episodes we did. I never felt that there was anything other than a great sense of freedom and a welcoming to just come and play in the sandbox and be idiots, and God knows we were.

On the spirit of the time…

It happened to have been a particular time that allowed more. There was less fear about results and less what I call this crazed ambition that people have now, and hunger. It was creator driven, but it also seemed to feel more collaborative than a heavy-handed creator-driven piece. There have been in the past and many, many more since that are much more, shall we say, anal, about how it all goes. The idea of it and the spirit of it was so open and so playful and it wasn’t driven by this hunger or this commercialism or this desperation to be something or to compete. It really did come from a creative place. That’s what it felt like at Hanna-Barbera in those years.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.