Session 23: Brain Scratch

For one month, The Dot and Line is publishing essays, interviews, and discussions about each episode of Cowboy Bebop, which turns 20 this April.

In one of the tales which make up the series of the Mabinogion, two enemy kings play chess while in a nearby valley their respective armies battle and destroy each other. Messengers arrive with reports of the battle; the kings do not seem to hear them and, bent over the silver chessboard, they move the gold pieces. Gradually it becomes apparent that the vicissitudes of the battle follow the vicissitudes of the game. Toward dusk, one of the kings overturns the board because he has been checkmated, and presently a blood-spattered horseman comes to tell him: “Your army is in flight. You have lost the kingdom.”

—from “The Shadow of the Players,” by Edwin Morgan

This parable—in this form, lifted from one of Jorge Luis Borges’s edited anthologies, which was introduced by the late Ursula K. Le Guin, called the Book of Fantasy—is one I return to often when thinking over my own line of work as a designer in the mixed realities space. It’s not a particularly shocking tale, and I suspect that the general shape of the message has taken on many forms in many media throughout time. But I do want to stress the ludic undertones of this piece. Why does it focus on games?

Games have a wonderful ability to enclose us in a so-called “magic circle,” whereby the otherwise stale, dusty objects that comprise a board game are elevated to a nearly metaphysical importance during play. Such circles, at least in the history of chess, were left uncodified for many years. There would be house rules, nuances and subtleties to the game that varied by region, and what have you. In my own head, I’ve often wondered what the house rules were for these kings that led them to ignore what the pieces actually were — real people.

One way to unpack this phenomenon is to apply philosopher Martin Buber’s notion of relationships: I-It and I-Thou. Put simply, Buber argues that people either relate to things in the world as objects or as people. So what happens when the house rules don’t let us address the humanity of others in technologically-mediated interactions? Have the rules changed? Has the house changed? Are there house rules at all when things become automated?

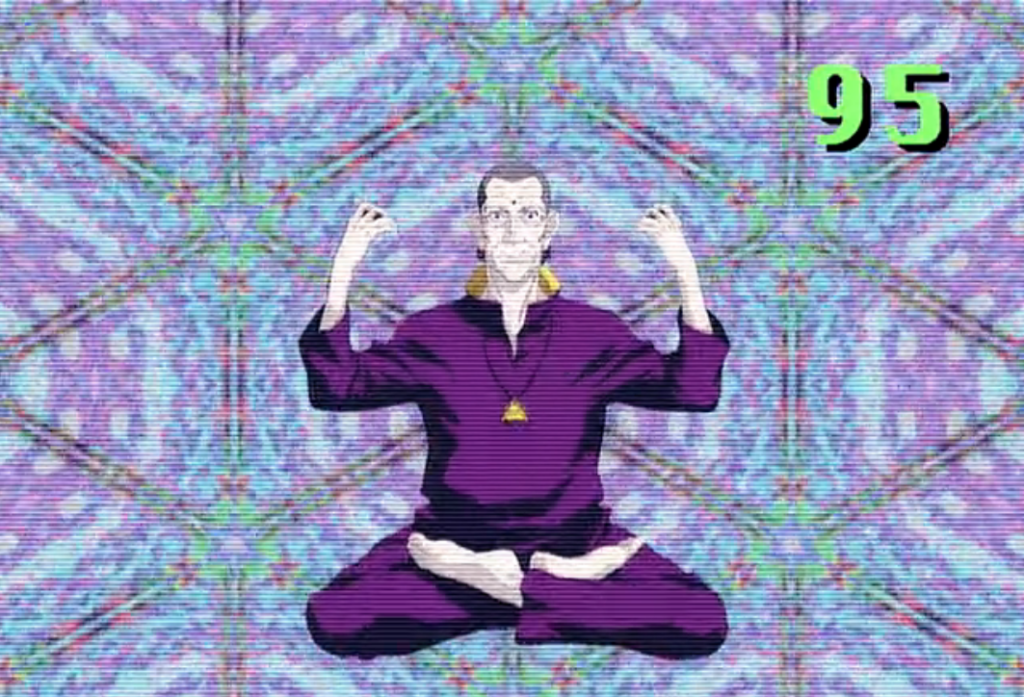

In “Brain Scratch,” we see an example where the culture of trust we have for designers — house rules — is challenged. In the episode, we learn that a VR headset supposedly created by popular neuroscientist and cult leader Dr. Londes negatively affects the brain in a rather short time scale. But long-term effects of the device on users are more insidious, as the slight adjustments they may make over time can go unnoticed. They may normalize attentional patterns and perceptions of others.

In many ways, the long-term conditioning is the most worrying sort, as this episode makes clear. And though we may not end up in such a dire situation as a “migrate to electronics movement” techno-cult, the real-life implications in this episode are clear: technology — even the very innocent chess board — is an opportunity to lose sight of what you value, or to value different things. And what is at stake in the interactive realm is the possibility that we mistake people for objects — not because of our own faults or another’s, but because the modes of communication do not celebrate this human-to-human contact.

I have compassion for Rosny Spanngen—the comatose hacker our bounty-hunting heroes learn is truly behind the Dr. Londes character—because I imagine others were not there for him when he needed it. I imagine that he might have been reduced to an object through the medical gaze, as if the magic had been lost and he had become removed from the chess board entirely. We learn from his alter-ego that the body is something like filth — the source of our problems. And, presumably, this is Rosny reckoning with his own medical situation.

But, in fact, the burden of responsibility for safe digital interactions rests on the designers who, in our case, is not one Dr. Londes. Instead, it is the burden of tech-culture writ large. It rests upon the shoulders of the gatekeepers of gaming communities who actively protect their digital spaces from diversity—those who maintain fixed rules and patterns of interaction.

Design culture encourages conflict over cooperation, prioritizes retention rates over meaningful experience, and sanctifies technologists over interventionists. “Brain Scratch” asks us to reconsider who is at the helm steering our use of technology. It also did so in 1998, a time when most of us weren’t quite immersed in a “sea of electrons.”

Now, though, I feel like I’m drowning. As a media maker, I have only grown more skeptical of the very medium I love. Game designers leverage immense power and exist in a depressingly privileged space. And from this privileged space — in one small sector of one half of the digital divide—it can be hard to see the humanity in others. Technology can prevent us from seeing the magic of intersubjective experiences.

I encourage all digital denizens, and game developers especially, to watch, or rewatch, “Brain Scratch.” Consider what the chess board looks like. What’s on it? What do the pieces represent? Is there a way to monitor how each chess move affects the world beyond the board?

If not, maybe there’s a way to illuminate the conditions that brought you to the game in the first place. And then, perhaps, you might dream up a sweeter world—for yourself and others.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.