Session 03: Honky Tonk Women

For one month, The Dot and Line is publishing essays, interviews, and discussions about each episode of Cowboy Bebop, which turns 20 this April.

Between student loans, credit cards, mortgages, and hospital bills, 73% of American consumers die in debt. I’m no brain genius, but that data suggests there’s a good chance I — and you — will die carrying some form of debt. That’s a fun conversation starter for a Tinder date, huh?

If you’re like me, a person who works just to live, who has to save for three months to pay a single month’s student loans bill, you wear debt like a heavy coat and occasionally expose the reality of the situation to remind people that this is not a healthy way to live, like a depressed flasher. There is a chance that someday I’ll be able to cross one debt off the list and the burden I carry will feel a little lighter, but that future is a grim one that holds in it the possibility of another debt on the horizon. Debt is as common today as syphilis was before the discovery of penicillin: everyone’s got it, it’s driving us all insane, and for all we know the cure could very well crop up in some moldy bread.

But until that cure comes — whether in the form of universal healthcare or the collapse of the student loan empire — the nature of debt in our society invites the question: who would you be if you learned to accept that you will never pay off your debt?

Cowboy Bebop’s Faye Valentine attempts to answer exactly that question, from her introduction in the episode “Honky Tonk Women” to others that flesh out her past like “Speak Like a Child” and “My Funny Valentine”—which explain that she was cryogenically frozen after an accident in space only to be woken up with mountains of medical bills piled up over 54 years. We’ve all been there! From the moment we meet her, Faye’s devil-may-care attitude and the steely armor she presents to the world are defense mechanisms central to her personality. But, like armor, these aspects of Faye hide from the world a person who is scared, isolated, and feels almost helpless in the face of a foe that is simultaneously invisible and ever-present. Debt, both for Faye and for the 73% of Americans who will die in debt, is less a number and more of an invisible force hovering overhead, bearing down. Faye’s actions are all driven by and against this invisible force, be it in love or friendship or in her recklessness. It’s hard to overstate exactly how vital those aspects of Faye’s character are — and what it means for how we exist with debt in the real world.

Like Faye, who you were before your debt is frozen in time and, ultimately, irrelevant and irretrievable. Even if you pay it all off, you have still shouldered a stressful burden that leaves you marked in a way those who’ve never had debt can’t understand. Within Faye lurks a careful juxtaposition between a reckless, gambling-addicted fighter and a vulnerable human seeking connection and an understanding of who she is. When she goes to the dog races in “Speak Like a Child,” her cheers for her chosen pup stand out as a jubilance greater than just wanting to win. She sees in gambling the chance to lessen her debt, to lessen the weight of it on her. And when her dog loses, she packs it all in, retreats within herself, and re-hardens back into casual apathy as the hope of being debt-free fades back into a tiny, hidden pocket in her heart.

And who Faye becomes — well, it’s a tribute to exactly the person many of us would become, I think, if we were in her circumstances. She carries herself as a disaffected badass who’s totally open to risky behavior because the worst that could happen is she dies and, with her life, so goes her debt. Yet there are cracks in her facade. In “Honky Tonk Women,” gangsters dangle the possibility of Faye paying off her debt to manipulate her into doing their bidding. In “My Funny Valentine,” she still feels a hopeful warmth toward old flame Whitney Hagas Matsumoto, despite the discovery that he 1. married her and faked his own death just to free himself from debt and 2. is just a con-man who has manipulated women all across the galaxy, so, like, 3. he probably didn’t even have feelings for Faye when he was conning her and faking his own death, which I would argue is the greatest transgression of them all.

The earliest sign of Faye’s vacillations between tender, fallible human and battle-worn baller come in her very first moments in Bebop. We are introduced to Faye in the medicine shop (“Honky Tonk Women”), where she walks in wearing a ridiculous and now-iconic yellow outfit that’s almost too obviously a reference to The Fifth Element’s Leeloo (someone equally thrown into the world with no memory of herself!), sunglasses (which she wears at night because she’s a rebel!), and smoking one of the shop owner’s cigars (smoking is baller, kids!). Without a single word, we can tell she’s probably not someone you want to mess with.

Her first character-signaling line, “You know the first rule of combat?”, is punctuated by her loading up a submachine gun and opening fire on the street outside, cigar clenched between her teeth, before she coolly answers: “Shoot them before they shoot you.” That’s one of the top most baller introductions to a character I’ve ever seen, second only to RuPaul in To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, when she descends from the rafters dressed in a sequined Confederate flag ball gown and goes by the name “Rachel Tensions.” Seriously.

In Faye, we see determination against insurmountable odds…

Faye’s introduction here quickly frames her as a John Wayne figure, if John Wayne was brave enough to wear booty shorts held up by a sort of thong-suspenders thing. And almost just as quickly, that all goes awry. The goons on the street that she was shooting at fire back. In short order, she is captured, and her debt — namely, the power that debt holds over her — is then used to force her into cooperating with a scheme at a casino. Her debt can be — and is— weaponized against her because her debt is inextricably linked to the hope of its absolution. That’s human nature! See, despite the likelihood that I’ll be one of the 73% of Americans who dies with debt, I still feel compelled to try to pay it off. Not because I ever will — what a joke! — but because there is something uniquely proud about the possibility that it may one day lose its power over me. It hangs over me as a constant reminder that I, free though I may want to be, am tied down. I am stuck. Fixed in place, unable to move toward the traditional hallmarks of adult life: I can’t buy a car or a home. (I mean, I make smoothies for a living, so I couldn’t afford those even if I didn’t have any debt.) I can’t save up for an emergency or a vacation, because my “savings” go toward my debt. The spaces where a person would normally plant seeds of prosperity and comfort are paved over with the cold, transactional demands of that hovering ghoul. And so, with Faye, with all of us, paying off debt holds in it a hope to someday reclaim ownership over your life — you’re only tied down by yourself, or by someone in a leather mask if that’s what you’re into. Make no mistake: debt is an ugly, threatening beast. But in every beast snarling its terror at us is the hope that we might be able to vanquish it. 73% of us never do. But, you know, that doesn’t stop Faye from bounty hunting and gambling in the hope the impossible might come true.

Faye frequently asks “Who am I?” and the question always appears in the context of having no memory of her life before she was frozen. As her story unfolds, Faye exists in a sort of endless loop: she asks the question less — and engages in more risky behavior — as she nears acceptance of being eternally debt-ridden, only for that very ugly and human feeling of “hope” to crop up, convincing her that maybe she can go back to that person — the person before cryostasis, the person before debt. For Faye, never does the question of “Who am I?” stop being about who she was and develop into “Who can I become?” and I think it’s this absence that most irks me about Faye’s character. In it is an unwillingness — and a fear — of moving forward, of mourning the past and taking a step into the great unknown, too held down by the immensity of her debt to consider the possibility.

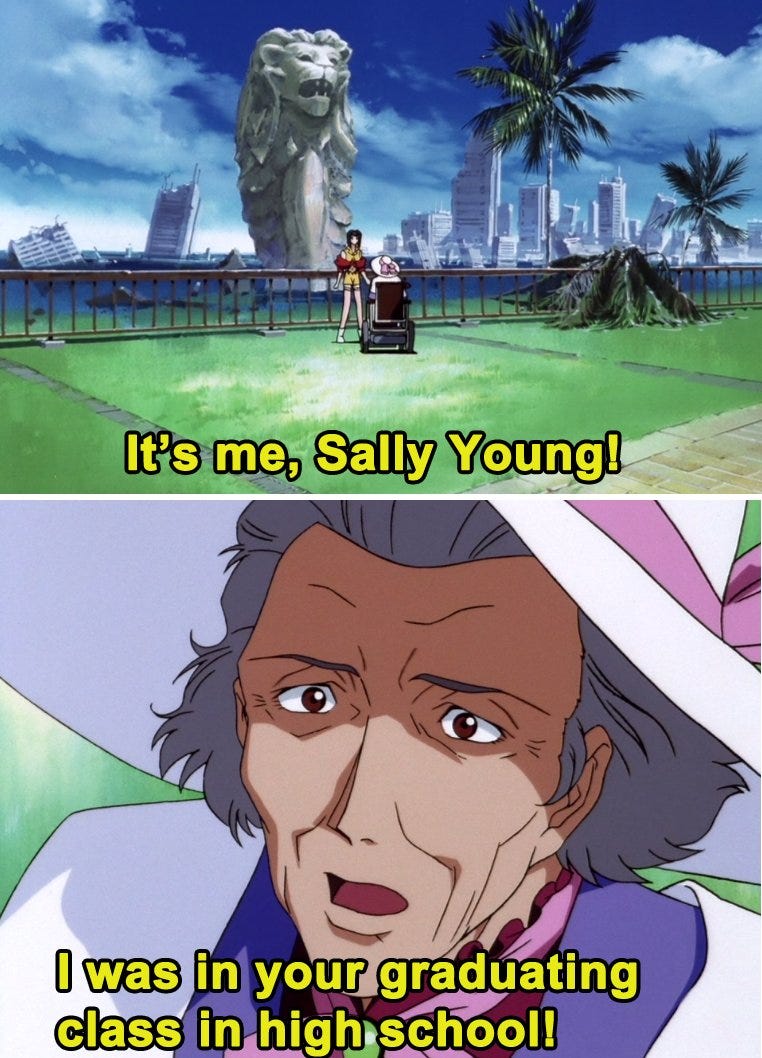

Her search for clues within the Betamax tape in “Speak Like a Child” lead her to seek out that past, only to discover that what she had and who she now is are so at odds with one another that it’s almost as if the past she struggles to remember is from a life that was never hers. In one of the last episodes of the series, “Hard Luck Woman,” when Faye sees her old friend Sally Young wheelchair-bound and looking many decades older than her, Faye immediately has a flashback to who Sally used to be rather than taking in who she now is. It’s a constant cycle for Faye, circling back to what was rather than accepting what is, in the same way I fantasize about a life without debt and poverty by holding onto my past experiences as a touchstone for what could be, since I have no measurement for who I’ll be once — if — I overcome my debt.

I understand wanting to reconnect with a past that you feel you’ve lost as the uncertainty of the future looms before you. I moved to the Bay Area in the far-flung hope I’d be able to reconnect with my father and establish a life for myself, only to realize too late that the Bay Area is suffocating itself in the midst of a rapidly intensifying cost of living, harshly contrasted with sluggish wage growth and stagnant housing development. I was so intent on rekindling a dead hope of my past that I threw myself into a financially volatile living situation. It took too long for me to realize that I never had and never would have a relationship with my father. For months, I mourned the death of that hope. Unable to hide from the loss, the effects of acknowledging it thoroughly affected me: my stress manifested in pockets of forgotten time, working 16-hour days six days a week, hardly ever sleeping, and, for some reason, routinely forgetting to lock the front door when I came home.

That’s the future Faye has to look forward to — a future of facing the ugly beast of defeat and mourning the loss of an irretrievable past — and it’s what she runs from every chance she gets. She’s a lot like Jay Gatsby in that regard, but thankfully nowhere near as obnoxious. And what’s more is that in some ways, she gets there. In small bits, in establishing herself as a mainstay on the ship, in her tenderness toward Edward, Faye creeps toward embracing the people around her and the misfit life she leads rather than staying stuck on the past that’s no longer hers.

The warning we seem encouraged to derive from Faye is that hope is a weakness that can be used against you. Time and again, Faye’s hope leads to heartbreak and she has to re-learn how to be cold and disaffected to survive. But beyond that, there is a beauty in Faye’s dilemma because it speaks so truthfully of the human condition. In Faye, we see determination against insurmountable odds, powered by a tender hopefulness mischaracterized as weakness, and the pain we must face in accepting that who we were is no longer who we are. Ultimately, in Faye, we get the answer to the question: If you learned to accept you can never pay off your debt — that you can never return to a once-golden, debt-free past — who would you be? The answer, it seems, is stronger.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.