Sessions 12 & 13: Jupiter Jazz, Pts. 1 & 2

For one month, The Dot and Line is publishing essays, interviews, and discussions about each episode of Cowboy Bebop, which turns 20 this April.

Space opera. Space noir. Space western. Cyberpunk? Kung fu flicks too? Sure, add ’em in. Not sure where we’ll fit it in the genre pile of categorization, but we’ll see what we can do.

Cowboy Bebop is often called, both lovingly and correctly, a cinematic pastiche. Its debts to both Western and Eastern films are enormous in terms of what it reveres, what it skewers, and what it simply collects. Sometimes I like to think of director Shinichirō Watanabe and screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto as cups awaiting rain, settled together in Sunrise Studios or maybe Studio Bones in 1998, endlessly flipping between channels playing Blade Runner and Chinatown and Enter the Dragon and Once Upon a Time in Mexico on loop, filling their ready heads to the brim with whatever pop culture trope brilliance might drip their way.

“Jupiter Jazz,” the show’s two-part mid-series finale, is no exception. It contains, in roughly chronological order, a Sitting Bull medicine man stereotype stand-in, a yakuza plot, a drug deal, a black-clad villainous cipher (or cipherous villain, take your pick) with a monotone rasp and a way-too-faithful henchman, that thing that happens in lots of animes where multiple old folks of high rank dress the same and speak in unison (if anyone actually knows the name for this trope — does it come from the noh or kabuki theater traditions? — please tell me), sepia-toned flashbacks, an ice planet, financial depression, quiet desperation, caricatured drag queen prostitutes, a smoky cool jazz bar, a charming and beautiful musician boy, goons in goggles and face masks, a femme fatale, a twist on the femme fatale, a psychologically tense shower sequence, a hero death fake-out, symbolic crows, a war buddy subplot, a military prison and crooked pharmaceutical company subplot, a betrayal by a former war buddy subplot, the line “death does not frighten me,” a kidnapping, more sepia-toned flashbacks, another femme fatale avec twist, a woman in a white dress and veil, a twist on a woman in a white dress and veil, lots of intense shots of people pointing their pistols directly into the camera, deadly loyalty, a spaceship dogfight, poetic justice by way of explosion, a moving and untimely death of a now-beloved character in which our hero learns just too little, and, finally, the return of the Sitting Bull medicine man stereotype stand-in, whose final lines are the same as his first and are now even more significant, as their prescience has been proved.

Does this sound derivative? It’s not derivative! I mean, it’s a pastiche, so it kind of is, but it’s more synthetically nuanced than just derivative, and that’s the point. All this cribbing matters. Cowboy Bebop was, by most accounts, the first anime to truly break through into American culture, in part because it was so rooted in American culture itself.

But it’s not just American (or indigenous American) culture and pop culture it pilfers. Older things live in Bebop too. It’s buried in myth, for one. As a keen-eyed and heady critic has made clear, the show is just as interested in the one-armed (well, one-natural-armed) Jet’s mythological link to the Norse god Tyr, and the one-eyed (well, one-natural-eyed) Spike’s mythological link to the Norse god Odin, as it is in jazz or the frontier. (An abstract I will forever wish I had written: “Who knew that Cowboy Bebop was basing its characters on Proto-Indo-European mythology? French philologist Georges Dumézil, that’s who!” My heart.)

And, more importantly, its interest is in timeless questions and emotions. What is past? What is love? What is a promise worth? What is friendship? Can we ever truly be alone? What is gender, and why? What does violence solve? Is memory a blessing or a curse? Can we ever escape our past? Why do we exist? Can we change? Do we have a choice?

There’s something that this cribbing does that makes the exploration of these questions feel almost paradoxically new, as if, through rebuilding a million somethings built a million times before in a million different ways in a finite space, it can transcend it all—the influences, the space, itself, everything. This show is like a meta-answer to the meta-question of originality in art. It almost makes the question of whether aesthetic recycling matters irrelevant in its first episode’s minute-long montage cold open.

And then it gives us two episodes like this.

1. Old Debts and Cold Sweats // Hoth-ward Bound

Imagine you lived a life before your life now. Reincarnation? Sure, maybe. Or maybe just reinvention. You needed to escape. To forget. You needed anything that was something but what you were once. To do this, you could change your name or change your work. Or you could run to nowhere. To a spaceship, maybe. Or a world where no one wanted to be.

Spike learns in short order that even a spaceship isn’t nowhere enough to hide from the past — all it takes is a few seconds of Ed surfing the web to summon up the ghosts of girlfriends past. Hearing the name “Julia,” he bolts, brushing off Jet’s confused entreaties, angry protests, and empty threats, and blasts off straight to the frozen moon of Jupiter called Callisto. The moon is Jupiter’s second largest, after Ganymede, and the third-largest moon in the Solar System after Ganymede and Saturn’s largest moon, Titan — the former Jet’s home satellite, the latter a former battleground during a nameless, mysterious war.

Single-biome planets are ubiquitous in genre fiction partly because they’re easy worlds to build, but also because constraint always breeds creativity—especially when the constraint of a landscape also provides your characters with constraints, or shows a lack of them. In Blood Meridian, for instance, Cormac McCarthy’s use of llanos and deserts and mountains brings a monstrousness out of the men weathering their climates, but Judge Holden, that unholy Miltonic toothy albino whale of a being who is, in fact, war incarnate, seems to have no issue. The Southwest and northern Mexico are not a single-biome planet—they’re not even a single-biome desert—but the barren nothingness of that space’s extremes operates with the same sort of brutality as any Tatooine.

Vicious, who is nothing if not Spike’s white whale, has a heart colder than any planet, we’re told, as he sneers his plans at his superiors in the Red Dragon clan. A poetic, and convenient, trait. But Spike, wrapped in his puffy pink coat to survive the frigid climate of Cowboy Bebop’s resident ice world, clearly does not. He must endure something, even if it doesn’t seem to bother him—or Faye, who doesn’t even wear pants, or the better-bundled Jet—all that much. Even so, we’re left wondering what it is Vicious has become to let him, like Lord Vader surrounded by his Snowtroopers on Hoth, stand unprotected on a desolate, frozen world that even our heroes must protect themselves from—one whose residents themselves are barely able to survive it.

On Callisto, Spike is put through the ringer looking for Julia on a poverty-stricken moon almost entirely devoid of women. (Single-biome planets like putting their visitors through the ringer. Just ask Luke Skywalker about the swamps of Dagobah—or the ice caves of Hoth, for that matter.) He finds a lead in Julius, a drag queen whose name a local had mistaken for Julia’s. Spike’s reaction to Julius’s winking proposal is one of surprise and disgust, something we’d generally not expect from a character typically so cool and collected. Following that rather disturbing reaction, an unfazed Julius tells Spike that his best bet is to try Gren, a saxophone player at a bar called the Blue Crow.

Both crows and the color blue have particular symbolic and emotional resonances, both in culture at large and in this show. But Spike doesn’t get much time to contemplate the nature of the blues or wonder which of Odin’s crows—Huginn (Thought) or Muninn (Memory)—might have inspired the jazz joint’s name. (Although this is Cowboy Bebop, so I think, of the two, one’s a pretty clear favorite.) After a little sniffing around, he’s cornered by a bunch of masked thugs who mistake him for Vicious.

Vicious is exactly what he becomes. Upon the accusation, Spike slams his fist into a metal pipe, literally shaking with anger. He loses everything even resembling cool, thrashing the would-be thieves and leaving their leader crumpled in the snow. Spike’s true self is normally almost inscrutable—his performed self, polished into the perfect semblance of apathetic and carefree, ensures that—but in these moments, a toxicity that circulates subtly under the surface begins to show itself.

That toxicity is a lot easier to see in Jet, who is more open in expressing his feelings, either vocally or physically. For Spike, though, this is one of the few times in the series in which he lowers his emotional guard—in part because, hearing the name of his long lost paramour, he’s forced to face the questions the show itself is asking. Just the utterance of Julia’s name sends him spinning into a flashback reminiscent of his first in the series, from “Ballad of Fallen Angels,” and with it, those questions almost seem to echo. What is past? What is love? What is a promise worth?

2. The Jazzboy of Jupiter // Gender Bender

Meanwhile, over at the Blue Crow, Faye is in full noir mode, dragging at a cigarette while staring into the distance as the dulcet tones of a tenor saxophone croon a cool jazz ballad into the smoky, dimly-lit room. She’s catching a cold, too, probably because she’s still wearing her usual outfit with only one added layer. She’s noticed immediately, especially since she’s on a moon occupied entirely by men but, as she later says aloud—and as we viewers know well by now—she can take care of herself.

Enter Gren, the smooth, swoon-worthy, sax-slinging jazzman whose tenor saxophone gives the two-part episode its title. His entrance, too, is classic noir: sidling up to the bar after Faye sneezes into her drink and as a tune of significance is played by a solo piano in the background, he throws his jacket over her shoulders, cooly delivers a pickup line that he proceeds to explain is not a pickup line, patronizes Faye, the little lady who clearly can’t handle herself in such a dangerous world of big, bad, mean old men, and then promptly loses the femme fatale—who, to be fair, he makes clear he’s not interested in anyway—to his own assumptions.

Then again, the audience—carried away by Gren’s dashing good looks and Dave Thomas’s subtle, suave voice acting in the English dub—makes some assumptions of its own. These are conclusions the episode, in a shower suspense scene worthy of Alfred Hitchcock, is ready to correct with a quickness.

Following a run-in with the same goons Spike left snot-nosed and bruised earlier in the episode—goons Faye easily could have handled—Gren comes through with his sax case and goes full White Knight, grabbing Faye’s hand and running her back to his place. There, she takes a load off while getting the full femme fatale bombshell visual treatment—one of many blatantly gender- and sex-focused shots in this two-part episode—and vents to Gren about solitude:

“I am alone. I don’t need any comrades. They’re not worth it. I end up worrying over things I shouldn’t. You know — me being such a prize and all that. All the guys end up fighting over me like dogs. They say humans are social animals, they can’t live alone. But you can live pretty well by yourself. I tell you: instead of feeling alone in a group, it’s better to have real solitude all by yourself. When I’m dealing with them, I swear it’s nothing but trouble. And I get nothing out of it. So it doesn’t matter if I’m there or not, right?”

There’s a lot to unpack here—specifically about Faye spinning herself as a “prize” for her comrades on the Bebop, which is (a rarity in anime) never the case. Faye is presented sexually through the series, but not as a sexual object; the show isn’t interested in Faye as a conquest, but as a player trying to stay at the table after being dealt a really bad hand, solitude and beauty in the man’s man’s man’s world of bounty hunting included. What is friendship? Can we ever truly be alone?

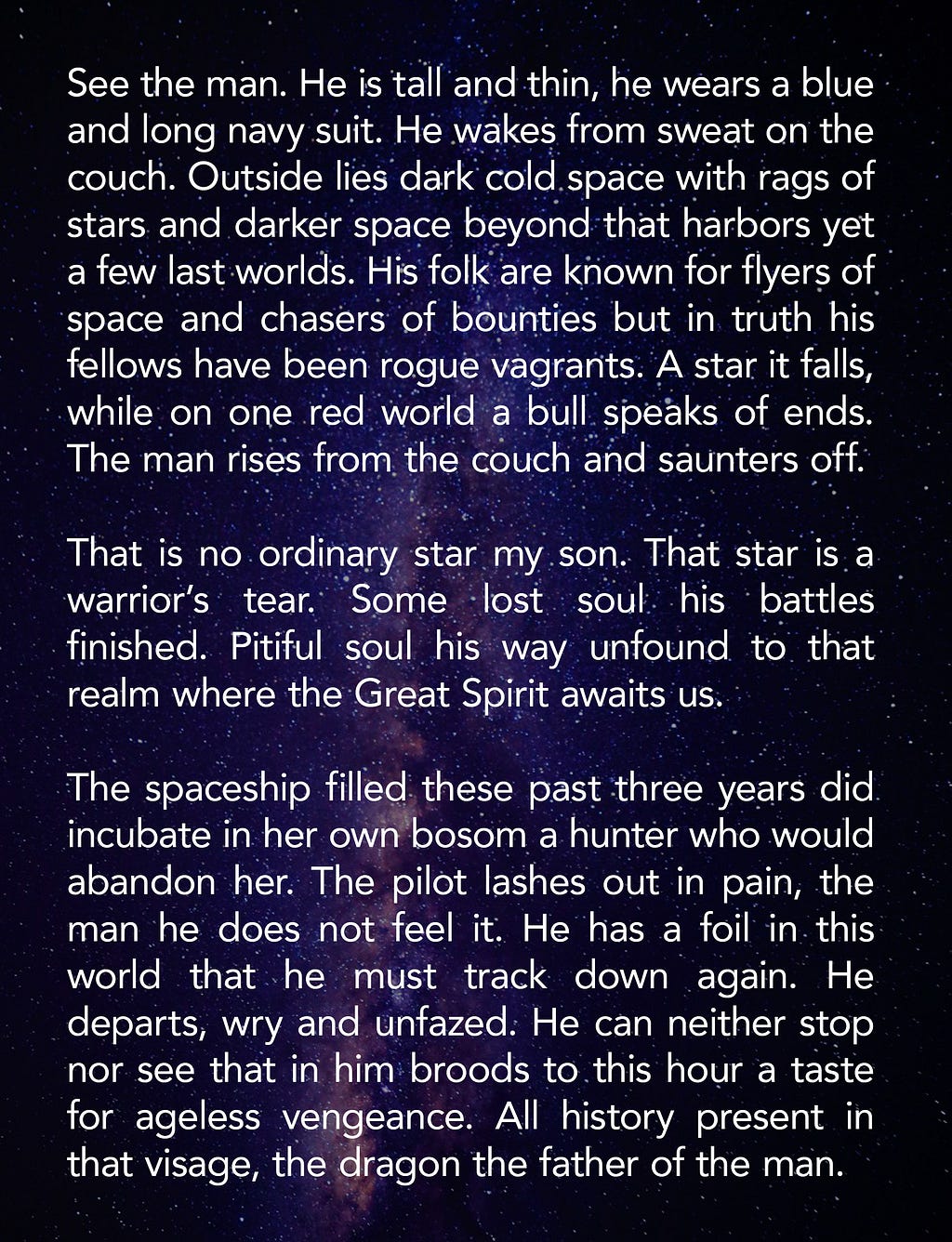

Later, while Gren is in the shower, Faye gets busy being her usual nosy self and sees a picture of Gren with Vicious in military uniforms—just as Vicious leaves a well-timed message in drug-dealing code on Gren’s answering machine: he’s on Callisto, he’s got some vials of a drug called Red Eye to sell, and he’s waiting for Gren to name the meeting place. Knowing firsthand that Vicious is deadly, Faye grabs her gun and heads to the shower. (Water is quite significant for Faye over her story-arc; it is a reminder of what she has lost, and who she is, and this definitely isn’t the only time a shower messes with her head.) There, she finds that Gren isn’t quite who he seems to be.

The shower scene revealing the complicated nature of Gren’s body is…well, complicated, mostly because the hormone imbalance that affected his secondary sex characteristics was not his choice. He—and his pronouns are he/him throughout, although, when describing his gender, he calls himself “both at once and neither one”—explains that he used to serve in the military in a never-quite-explained war that took place on Saturn’s moon Titan. There, he was stationed with Vicious, who saved him from death by scorpion sting and made a gift of his music box at Gren’s request. (That ballad Gren was playing in the bar? Well, it’s the tune from Vicious’s music box. Its name? What else? “Julia.”) When, why, and how Vicious got involved in the military is, like the war on Titan itself, left opaque, as if the whipping sands of the brutal moon left all reasons lost to memory.

All that’s clear is that Vicious betrayed Gren’s trust following the war, framing him as a spy and testifying against him in court, ensuring that he was sent to military prison. There, Gren went insane from the isolation and the sheer shock of his betrayal—was Gren in love with Vicious? I think probably yes!—which prompted a pharmaceutical-industrial complex intimately connected with the military in which Gren served to use an experimental antipsychotic on him. (Across town, Jet learns a little bit about Gren, too — specifically that escaping from that military prison has put one heck of a bounty on his head.)

That antipsychotic, Gren explains, made his hormones go haywire. As he recounts this, the animation moves to a panel of Faye holding her gun, like a phallus, between her open legs. What is gender, and why? Still, the antipsychotic returned, it seems, some sanity to Gren, leaving him only with burning questions. Why would Vicious betray him? Weren’t they comrades? How could someone he had once served beside, whose life he even saved, mean nothing to him?

Vicious’s motives here remain deliberately unclear. It almost seems that his vendetta against Spike isn’t as special as we’re led to believe. He aspires to power, but why? No motive is ever given. Later in this episode, he even says “there is nothing in this world to believe in,” as if even he believes in nothing. But not all nihilism ends in the sort of wanton, murderous bloodshed Vicious engages in. Spike’s certainly doesn’t—at least not when he can help it. It’s almost as though Vicious has bought, wholesale, the philosophy of McCarthy’s Judge.

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

Vicious certainly has a knack for warfare—not only does he actually serve in a war, but nearly every life he directly touches afterward, by season’s end, is destroyed fundamentally on some level. What does violence solve? For Vicious—or, better yet, for war incarnate—does it matter? Violence simply is. Beware the nostalgic fool who steps into its gore-torn path, whether his name be Gren or Spike.

3. Dreams of Dovetails // Eating Crow

Our favorite of those fools is lucky that it is not war itself, but merely one of its pawns, Lin, who shoots him toward the end of “Jupiter Jazz, Pt. 1.” We learn, in “Jupiter Jazz, Pt. 2,” that he’s merely been tranquilized. There, paralyzed and knocked out, he’s trapped between life and death, and a flashback sequence elaborating on the one from “Ballad of Fallen Angels” ensues. It’s almost too on the nose—even when he’s back on his feet, Spike is in stasis, paralyzed by the past while lurching almost without control toward a future rooted in it.

Almost like this episode, in fact. Typically, mid-season finales—especially in shows that are loosely, rather than purely, serial—have it rough. Since they are, almost by nature, begun in medias res, they need to tell 1. an encapsulated story that 2. ties into the series arc while 3. revealing enough to feel significant but 4. not too much as to feel rushed or spoiler-laden and 5. still foreshadow what is yet to come while 6. not letting go of what has already happened and 7. they typically need to pull it off in the runtime of one or two episodes, max.

This is part of why the use of that ageless binary of good and evil proves to be both fine tool and tempting crutch for those who would tell a story. As McCarthy might put it, each comes pregnant with its own significance from which none can be untethered and that significance lends its color to all that is touched by either. And while Cowboy Bebop is less interested in morality than it is in purpose, it certainly employs its own ethical binary, even as it undoes it. Spike, rash shitbird purposelessly captive to his own past though he may be, is clearly the Good Guy here, if only because Vicious—whose name would be enough to convey his general antipathy even if his motivations weren’t clearly neutral evil and his character build wasn’t a Sephiroth carbon copy—is so clearly the Bad Guy. That’s part of what makes what ties them together so interesting.

As the snow begins to fall on good and evil alike at the end of “Jupiter Jazz, Pt. 1,” the faces of both Spike and Vicious are framed closely by the camera—with an emphasis on Spike’s left eye and Vicious’s right. Spike’s left eye, of course, sees the past, which is filled with evils that haunt him, and it’s often visually accented often whenever he’s confronting his past. (Earlier in the episode, when he hears Julia’s name attached to Vicious’s operations, he drops a cigarette from his lips in shock as the left side of his face is framed in profile.) Vicious is one of those evils, and his face here is framed so as to focus on his right eye. What a twist in imagery! The right eye—correct? just? true?—is stressed on the villain, while the left eye—the “sinister” eye—is stressed on the hero.

Then, of course, there’s this shot-reverse-shot in their confrontation:

“I’m the only one who can keep you alive,” Vicious tells Spike in a flashback that recurs throughout the series, “and I’m the only one who can kill you.”

And maybe that’s true. Luke, after all, is Vader’s son—the one seems fated to determine that of the other. For Spike and Vicious—former soldiers of the same syndicate (“comrades,” to borrow Gren’s word), former lovers of the same woman, and former brothers, in a sense—the similarities are almost as pronounced as the differences, and in those similarities they seem tied inextricably. Recklessness rooted in reminders. Bloodshed as a solution that nonetheless continues to breed new problems. An unwillingness to let go. What does violence solve? Is memory a blessing or a curse? Can we ever escape our past?

In “Ballad of Fallen Angels,” Vicious compares Spike to an animal.

Vicious: You should see yourself. Do you have any idea what you look like right at this moment, Spike?

Spike Spiegel: What?

Vicious: A ravenous beast. The same blood runs through both of us. The blood of a beast who wanders, hunting for the blood of others.

Spike: I’ve bled all that kind of blood away.

Vicious: THEN WHY ARE YOU STILL ALIVE?

We see a bit of that in the aforementioned scene from “Jupiter Jazz, Pt. 1” in which Spike’s anger at being mistaken for Vicious drives him into a blind rage. We also see it when he’s on the hunt for Vicious, gearing up with extra artillery as in “Ballad” or, here, attempting to corner his nemesis in the dark.

Vicious’s point , too, feels like McCarthy to a T. For his Judge, there is no answer but war, no end but one that comes with blood, no survivors but he who becomes the end of all others.

“Hear me, man, he said. There is room on the stage for one beast and one alone. All others are destined for a night that is eternal and without name. One by one they will step down into the darkness before the footlamps. Bears that dance, bears that don’t.”

Again, the frigid climate of Callisto, like the red oven of McCarthy’s Southwest, seems custom-tailored to accenting this message. In places like this, survival can only occur when no cost is too high. Here, there is significance in every action. Every move. Every relationship or destruction thereof.

And yet there is Gren, who remains, too, twinned to Vicious. Remember: Luke may have been Vader’s son, but Vader also had a daughter of no small significance. And a lover, too, if you count the prequels. And a master—a relationship even Vicious acknowledges in “Ballad,” although he chafes against it. Loki, blood brother of Odin, does not kill Odin, but Baldur, for which Odin punishes him but does not, and cannot, kill him. Even those who want it to be one way sometimes cannot help but find that it is, in fact, the other way. Gren even acts like Spike when he talks about Vicious. He’s just as wrapped up in a Vicious-centric betrayal, for one. Then: “Death does not frighten me,” he tells Faye in his apartment. Now, who does that sound like?

These episodes are just stuffed with dualities and parallels. The crows that fly over Spike and leave their black feathers on the ground beside him dovetail all too neatly with the doves, white as Callisto snow, that accompany Julia in flashbacks. Faye sits on the same stool at the same bar Julia occupied when she, too, came to Callisto. Julia became Gren’s close companion—almost as close, it seems, as she was with Spike or Vicious.

Then, of course, there’s the gender-flipping treatment, Gren’s breasts accented along with his crotch while wearing a white, almost wedding-like dress to meet Vicious for a drug deal—where, as always, Vicious is dressed in all-black, the would-be bridegroom. Was this the scenario Gren had hoped for all along? The control console of Faye’s ship protrudes from between her legs as Jet—having found her handcuffed to Gren’s bed (but decidedly not in that way)—tows her back to the Bebop. And, at episode’s end, Spike holds Gren in his arms as an echo of that song, “Julia,” plays behind them. Holding him as we imagine he would have done with Julia so, so long ago, and as Gren might have wanted from Vicious. They are new comrades together just as both were comrades to Vicious once—a circle made whole, or, perhaps, wholly broken.

Spike’s big question for Gren may have been where he could find Julia, but after he doesn’t get the answer he wants, he still grants Gren his dying wish. Is it out of loyalty? Charity? Well, maybe it’s both.

4. Space is the Place // Finding the Lion

Why do we exist? Can we change? Do we have a choice? These are, I think, the questions Cowboy Bebop asks at its core.

Vicious has his answers: “There’s nothing to believe in. There’s no reason to believe. There is nothing in this world to believe in.” They are not too dissimilar from those of the Judge. For what does war in its most pure form leave, in the end, if not nothing? Vicious exists because he can, kills because he can, stays the same because he sees no reason not to. He lives for nothing, and all around him will too, if he has his way. (Poor, doomed Lin, so dedicated to an order whose rising power could not care less for his existence, finds his answer, too, dying in unappreciated service as befits his life.)

Gren has his answer, too: camaraderie. “Do you have a comrade?” asks the episode in lieu of its typical “See you, space cowboy” sign-off. Well, Gren didn’t—he lost Vicious—but in the end, in Spike, he did. Spike could do for Gren what Vicious never would have. He could help him, unselfishly, back to Titan, where he had gained, and lost, so much of what made him who he is. In Spike, Gren found a comrade who would take him home. And so he does, dragging Gren’s ship (like Jet did Faye’s) into space and launching his dying body out of Jupiter’s orbit toward Titan’s sand-swept surface. Bye bye, bounty.

Sturdy Jet continues supporting his comrades, letting lesser infractions go—because he can and, as a self-styled provider, because he must. Faye, whose journey in this episode was really to learn about her own comrade, finds a new purpose in new curiosities, new questions—wondering about Julia, about Spike, about “something very good.” Ed finds satisfaction in the moment, as she always does, painting Faye’s toenails and prompting what might be, quietly, one of the most profoundly emblematic lines of the entire series: “Oh, Ed. Anything but blue.”

Laughing Bull and his son sit and watch the stars as one falls — signifying, Bull says, the death of a warrior, whose soul is condemned to never reach the “lofty realm where the Great Spirit awaits us all.” Bull’s son has no answer, yet — young and inquisitive, he can only ask. Bull has known his answer — perhaps the answer — for what seems like time immemorial. We exist because we exist. We change because we change. Choice has nothing, and everything, to do with it.

And Spike?

No. No answers. Spike simply carries on, a resigned smirk on his lips as he returns to the Bebop—as if there was ever any real question as to whether Jet would, after kicking him off the ship at the episode’s beginning, let him back aboard. It’s not Spike’s turn for answers yet. Myths never end in medias res. They only end when they end. That’s when the hero—lightsaber raised, horse pointed toward the vast and gleaming desert, shield emblazoned with a crow in flight or, perhaps, a roaring lion—meets his fate. That’s when he has his answer.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.