It has been just over two weeks since the last mass shooting in the United States of America—meaning, of course, that the news cycle has moved on from NRA-sponsored governmental refusal to address gun laws that allow these murders to happen. The country, however, has not moved on. It is still murdering itself. It has been since 1966.

While a spree killing by gun occurred in Camden in 1949, mass shootings as we now know them began with the University of Texas tower shooting, during which Charles Whitman — a former marine, an Eagle Scout, and an architectural engineering student — positioned himself with a rifle at the top of the tower of the campus’s main building and murdered 16 people and an unborn child, in addition to wounding nearly twice that number non-fatally.

Former Texas Monthly journalist Pamela Colloff has spent a good chunk of her career exploring the massacre—which UT did not memorialize for 50 years—in stories that look at the impact of the event on one life and on many. It’s been noticed: her 2006 story, “96 Minutes,” an oral history rounding up testimonies from, as Colloff puts it, “three dozen people who got shot, fired back, lost loved ones, saved lives by risking their own, and otherwise witnessed the nation’s first mass murder in a public place,” was adapted into a full-length animated feature film, called Tower, last year.

“I really wanted to capture the visceral sense of what it was like to be there in the shooting.”

Colloff’s feelings on it were not mixed. “It makes me cry every time,” she messaged The Dot and Line on Twitter. “I loved how the animation takes us back through time and makes us feel the immediacy of events that happened over half a century ago, as though they were happening in real time.”

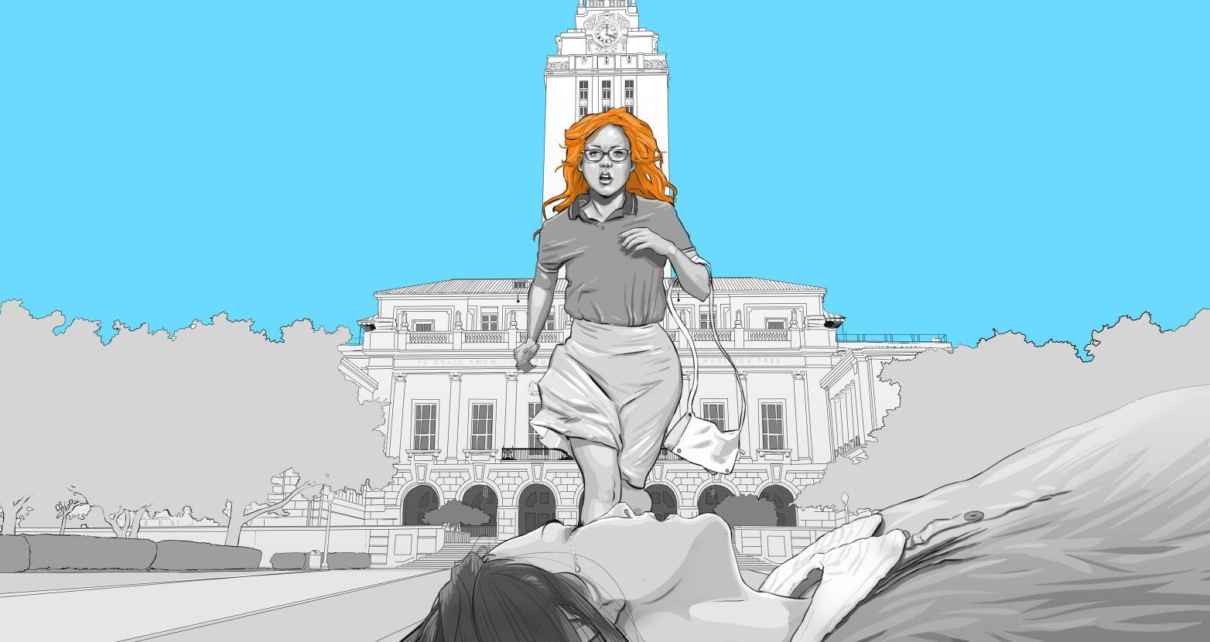

Keith Maitland, the film’s director and a UT graduate, said that choice was deliberate. He wanted whatever film he made about the event to be set on campus, but “knew the University wouldn’t let us shoot recreations.” There was another issue: the age of the interviewees—nearly 10 years after the 2006 article—prevented them from acting out the actions of their younger selves. That’s what made Maitland turn to rotoscoping—filming actual actors and then animating over them.

“I really wanted to capture the visceral sense of what it was like to be there in the shooting,” he said. “I knew before I finished the article that I wanted to make a film about it…. Because it’s rotoscope, it allowed the emotions and the humanistic portrayal of the young actors performing the roles to shine true. It was an incredible opportunity to be impressionistic and humanistic at the same time.”

Maitland grew up in Texas, but he heard very little about the massacre. Texas schools didn’t teach it, despite a mandatory Texas history course in middle school, and UT didn’t talk about it. Maitland happened to once have a teacher who told a firsthand account to Maitland’s class. But other than that, he learned little up until Colloff’s 2006 article. The film’s intent, he said, was to ensure that the story was as powerful on a personal level as it was on a historical one.

“It’s so easy, when we see these sort of news stories pop up on the screen, to keep track of the numbers: how many people shot, how many people were killed,” he said. “But to, for more than a few seconds time, empathize with people and put yourself in their shoes is something I think we’ve really done.”

For that, Keith credited lead animator Craig Staggs, whose renderings, at Keith’s request, focused on the eyes. “I knew,” he said, “the story would be told through the eyes.”

The film, which includes both animation rotoscoped over live actors and 15 millimeter archival footage of the events of that day in 1966, was put together meticulously. To ensure visual accuracy, Maitland and his crew collected photos of the victims from 1966, looked for actors who resembled them while also ensuring that those actors could approximate, Maitland said, “the essence of their character through their performances.”

It was in doing just that that Maitland realized that the film, while about a historical event, was also about something more.

“I thought we were going to tell a story of mass shooting. But really the story we told was one of overcoming trauma,” he said. “I think we all have events like that in our lives….Everyone has a story that they carry with them that changed them, especially at a young age….People have come up to us at Q&As and that’s what they expressed to us, that it helped them sort of deal with survivor’s guilt.”

While the archival footage was important for this, Maitland maintains that animation was, in the end, the perfect form through which to tell this story.

“I knew animation had a dreamlike quality, and part of what makes that poignant is it invites empathy in a unique way,” he said. People rarely use animation to showcase traumatic action the way Tower does, but we’re not alone. There are other films that do that, and more and more we’re starting to see that. I do think it’s part of the magic of animation, and hopefully that doesn’t go away.”

Learning about gun violence is important. Stopping it is more so. Donations or involvement would be welcome at some of Maitland’s suggested charities: Texas Gun Sense, Moms Demand Action, and Everytown for Gun Safety.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.