The 47th Annual Annie Awards are this weekend! And, just like every year that the awards have been held since 1972, one of the awards presented by the Los Angeles chapter of the International Animated Film Society, ASIFA-Hollywood, will be the Winsor McCay Award. Wait! Who?

“Eric, ol’ buddy ol’ pal,” my co-editor John Hughes Maher III—he of copious animation knowledge and little time to devote to discursive explanations of artistic ephemera—turned to me and asked, “who the hell is Winsor McCay?” (Editor’s note: Listen, wise guy, John knew who Winsor McCay was.)

Sitting at my computer, I cocked an eyebrow and replied: “Beats me, my bosom bro, but I bet I know who knows!” (Editor’s note: C’mon, Eric knew too. Whadda we look like, amateurs?) So I cracked my knuckles and fired up my Google dot com machine. What I now know about Winsor McCay is the fact that he was born in the years following the American Civil War and straddled the centuries to go onto work for William Randolph Hearst and in fact went on to pioneer several techniques in animation that are today taken as a given in the animation process.

He and his teams created 10 films in the decade between 1911 and 1921, though much of their output has been lost to time and the sad attrition of poor archiving. But the work McCay accomplished was nothing short of extraordinary, and much of it is available to watch via the Internet Archive.

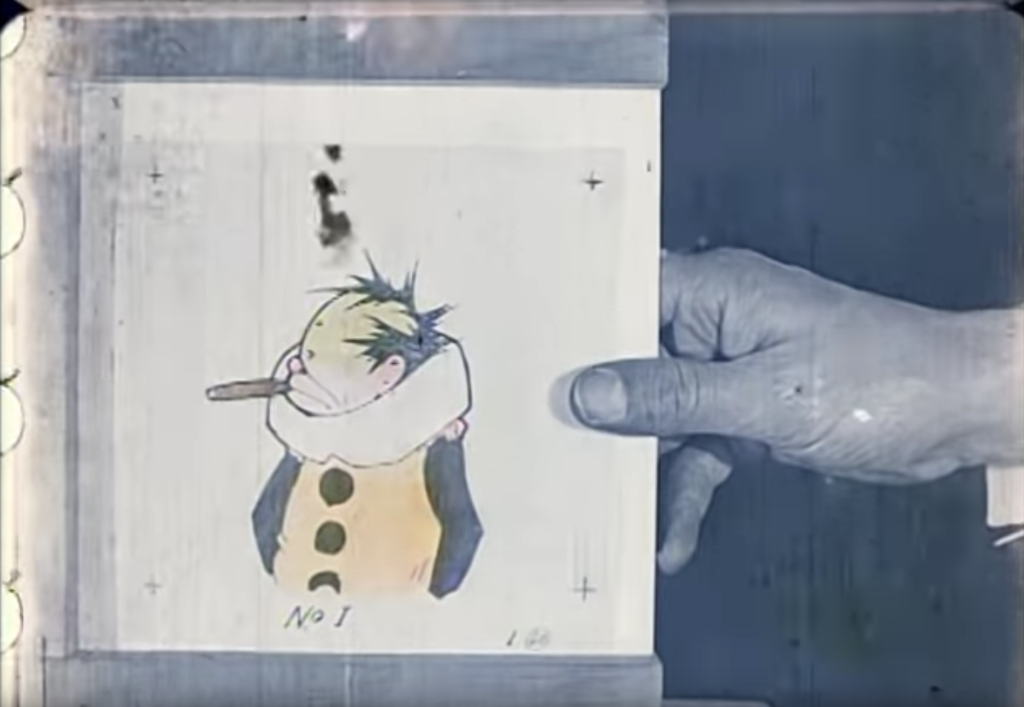

The first of such works was an 11-minute film titled Winsor McCay: The Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics, but more commonly referred to as Little Nemo. Little Nemo was McCay’s most famous creation, a character developed for early comic strips in the now-defunct newspaper the New York Herald. (It later inspired an influential, if under-acknowledged, anime.) The animated Little Nemo is an early and very meta example of a comic strip adaptation, depicting McCay’s illustration of characters in a newspaper office as they come to life in color and pioneering character animation while he was at it. After it screened in theaters, McCay went so far as to incorporate the animation in a live vaudeville show, interacting with the film as it played in an early example of multimedia art.

It really is remarkable to think that McCay did this well over a century ago, and then did it another nine or so times on other animated films he managed to complete, like The Sinking of the Lusitania (an early example of an animated documentary, even if it was a piece of propaganda) and How a Mosquito Operates (a cartoony study of a skeeter at work). He completed a total of 10 animated films and planned an additional three, but was not able to finish them. Despite the fact that several of his films are lost, few artists came close to his prowess or mastery of technique until the Fleischers, Ub Iwerks, and Walt Disney came along years later.

That’s why McCay, who remains more recognized for his comics, gets an animation lifetime achievement award named after him, in recognition of artists whose contributions to animation have penetrated our world views on the art form. Notable recipients include the dudes mentioned above but also Matt Groening, Bruce Timm, Katsuhiro Otomo, Andrea Romano, Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis, Caroline Leaf, Mamoru Oshii, and Stephen Hillenburg—to name just a few. This year’s recipients will be the late Satoshi Kon, Henry Selick, John Musker, and Ron Clements.

To this day. McCay rests in Brooklyn and Queens’s Cemetery of the Evergreens, alongside several other notable and creative New Yorkers. And you should watch all his available clips and read through the rest of his Wikipedia, because I really just scratched the surface here. Enjoy Slumberland, you dinks! Now youse know some of what we know! Don’t let it inflate yer melons!

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.