Of all the new characters introduced into the Avatar canon in The Legend of Korra, perhaps none left quite as strong an impression as Amon, the main antagonist of the show’s stellar first season. As the leader of the Equalists — a radical group of nonbenders whose primary goal is ridding Republic City, and eventually the world, of all benders in the name of equality — Amon is one of the most compelling and intimidating characters in the Avatar universe—a presence so strong that even after his departure at the ending of season one, he quite literally looms over Korra’s character and every other villain that follows like an ominous shadow.

Amon is not like most villains. Unlike Avatar: The Last Airbender’s Fire Lord Ozai, he is not pure evil made manifest. His logic for desiring the end of bending is understandable, if flawed—at times, it’s even sympathetic. And also unlike the hot-tempered Ozai, Amon is cold, calculated, and strategic. His words are carefully chosen, his actions meticulously made, his image and voice—provided by the incomparable Steven Blum, of Cowboy Bebop’s Spike Spiegel fame—shrouded with mystery and bearing an emotionless certainty that makes him nearly impossible to read and all the more terrifying when our heroes find themselves face to face with him.

But perhaps what makes Amon most compelling is the influence that real-life historical figures had on his character. Like many dictators and revolutionaries throughout history, Amon’s villainy is insidious precisely because of the way he deploys his seemingly idealistic viewpoints to convince and inspire those around him. He motivates his followers not with fear but by making them feel as though their voices are finally being heard—when in fact, he is always in service of his own agenda, one that lurks beneath the surface of his dedication to his followers and their beliefs. His preaching against all benders creates a convincing “them vs. us” oppression narrative that we continue to see in both U.S. and world today, and his stance on forcing equality at all costs directly mirrors Stalin’s Soviet Russia, which is also evoked via strong visual cues.

Although Amon is clearly a flawed figure, it is also not hard to imagine what an alluring, even inspiring icon he may appear to be to those who cannot wield the same powers of a bender in a world constantly reshaped by them. Yet by season’s end, the audience learns that Amon’s oppressive and manipulative nature and the lies behind his narrative.

Amon’s entire movement is built upon the premise that as a child, a firebender killed his family and left his face mutilated and scarred. By the end of Korra’s first season, it becomes clear that this is a fabrication. Amon is no nonbender but a waterbender named Noatak, the son of infamous Republic City gangster Yakone. His unbelievable acrobatic skills and ability to take away others’ bending abilities were not bestowed upon him by some divine hand. Instead, the man who so forcefully condemns bending is a bender himself, of the most fearsome variety: he is a powerful bloodbender, like his father before him.

If anything, this twist makes Amon’s real backstory even more tragic. As we learn through Tarrlok, Noatak’s younger brother and Republic City’s most deceptive politician, Amon was not born a monster—he was molded into one courtesy of the shocking hardships and abuse heaped upon him by his father. It’s this sorrowful family dynamic that makes Amon into one of the Avatar universe’s most compelling characters.

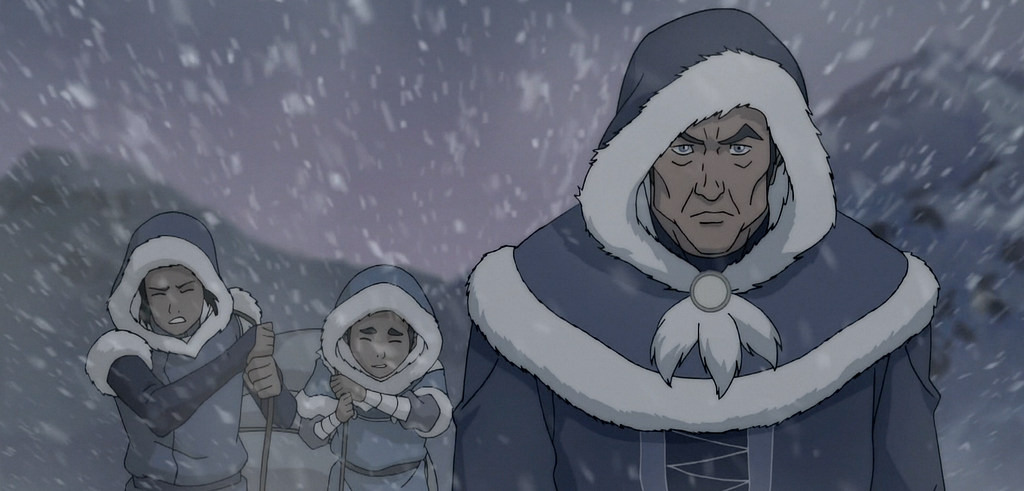

Amon’s story begins long before the events of The Legend of Korra, back when Aang was still Avatar. After his capture, the notorious crime lord and bloodbender Yakone is stripped of his bending by Aang, but escapes Republic City and relocates to a small village in the Northern Water Tribe. There, in what seems like an effort to reform, he meets a Water Tribe woman and together they start a family—first with Noatak and, later, with Tarrlok.

Early on, Noatak’s family life is tranquil, simple, and happily normal. The two brothers play and take care of one another as their parents watch proudly from the distance. But once Noatak and Tarrlok develop waterbending, the good days are firmly behind them. Yakone’s greed quickly takes hold of him once again, as he sees his sons’ abilities as his chance to take revenge against Republic City and the Avatar. He wastes no time in molding them into his own corrupt image, taking Noatak and Tarrlok on routine “hunting trips” during which he can isolate the two boys from their mother and secretly train them in the ways of bloodbending.

While Tarrlok struggles both morally and physically to gain his father’s particularly rare psychic bloodbending techniques, Noatak is an instant prodigy. He is able to naturally adopt the skills his father once honed, but as a result of his training, he becomes a shell of his former self. The warm, caring child Tarrlok looked up to had vanished. In his place was a callous young man who neither seemed to enjoy nor condemn Yakone’s teachings: instead, he simply embraced the brutal nature of his upbringing. A perfect fit for the most inhumane form of bending.

Yakone forces the boys to bloodbend wild animals, and each must bear witness to the pain and forced movements that comes with unnaturally controlling another creature’s life. If either resisted during the process, Yakone would verbally — and we can assume physically — abuse and barrage his children until they would comply. Yakone is a case study in toxic masculinity, using patriarchal expectations (“Toughen up, Tarrlok. You’ll need a thicker skin for this.”) and familial pressure to force his sons to his bidding.

That is, until Yakone forces them to practice bloodbending each other.

When asked to bloodbend his brother to please his father, Noatak does so without hesitation. But Tarrlok cannot stand it, finally condemning the practice and the pain it brings others. And just as Yakone is about to unleash his paternal wrath, Noatak finally turns on Yakone, bloodbending him instead and declaring his intentions to run away. He asks Tarrlok to join him, but Tarrlok hesitates, and Noatak declares that Yakone is right about him, calling him weak and indecisive.

The moment is a defining one for a particularly brutal family dynamic. Noatak clearly cares about Tarrlok more than anyone else, and is willing to defend his brother in a moment of crisis, but is also overrun with his father’s anger and desire vengeance and has been numbed to the value of human life. Noatak runs away — taking with him his father’s last hope of revenge — and for years, Tarrlok assumed his older brother was dead.

Years later, when both men seem to have escaped their father’s machinations, Yakone’s teachings are still what drives them, in spite of their different motivations. Tarrlok becomes a corrupt politician who manipulates and shifts any narrative he can in order to further his own ambitions. He uses the paranoia surrounding the rise of Amon’s Equalist movement as an opportunity to further his own power, unjustly passes laws that discriminate against nonbenders, plants false evidence and conducts aggressive raids that only increase mistrust, and shifts the blame among his allies as best suits his needs.

Meanwhile, the newly-named Amon forges an identity as an anarchical savior of the people. He lies about his past and his purposes to gain the trust of an oppressed society, creates his own falsehoods to deliberately further the cultural divide, and wreaks havoc among benders with his mysterious physical advantages. The two brothers may have ended up on different sides of the law and society, but their spiteful actions perfectly mirror each other. They are truly two sides of the same terrible coin.

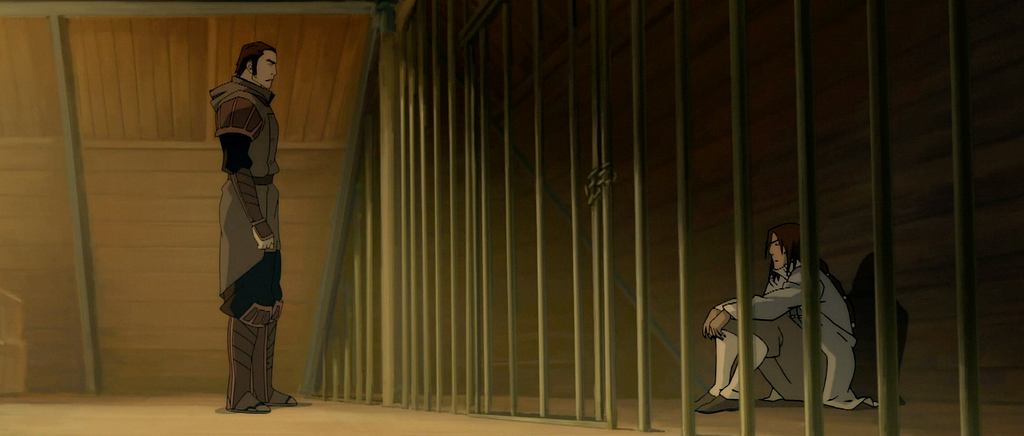

At the end of season one, both Tarrlok and Amon find themselves caught, defeated, and with nowhere to go. Amon, now known to Tarrlok, visits his brother in his prison cell and offers a new chance to escape — similar to the same offer he made when they were boys. Although the two used whatever means necessary to oppose one another throughout the season, in the end, all they have left is their brotherhood—a history rooted in the hateful teachings of an abusive father figure who ingrained his vengeful practices into their very being. “Our father set us on this path,” Tarrlok tells his brother. “Fate caused us to collide.”

As Noatak and Tarrlok escape in a speedboat, Noatak seems rejuvenated by the promise of finally being able to live a life with his younger brother. But Tarrlok knows the truth: there is no life for them. The two have done too many terrible things, ruined too many lives—to simply sail off into the sunset would be a kind of twisted joke. Both are broken men who have known nothing but suffering and hate as long as they can remember. It has been so long that Noatak sheds a tear at the sound of his own name. As Tarrlok grabs one of the Equalists’ signature electric-shock gloves and holds it over the boat’s fuel source, he affirms his brother’s affections. “It’ll be just like the good old days,” he says. Then he sets the ship ablaze, and it all ends. Because, as in all tragedies, the promised days of peace and joy have been rendered unattainable. The only peace to be found is in the flames—an ending so brutally moving as to cement both brothers’ places among the most complex and devastating characters in all the world of Avatar.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.