AIF Chats

Part of a series of chats we had with directors at the Animation Is Film Festival.

Even in the increasingly strange and imaginative pool of animated features that have captivated worldwide audiences throughout recent years, Birdboy: The Forgotten Children stands out as unexpectedly original. Based on director Alberto Vázquez’s 2011 graphic novel of the same name, Birdboy is a modern fairytale that follows a cast of creatively drawn teenage animals planning an escape from a bleak, post-apocalyptic island wasteland. The story covers a range of mature themes with a playful cynicism and intense visual language that ranges from depression and addiction to environmental disaster and even police brutality.

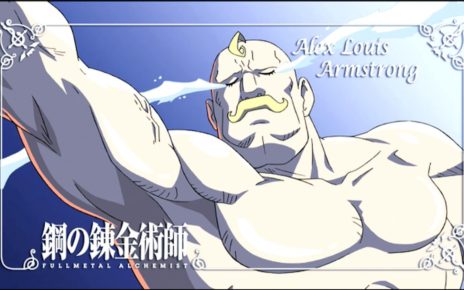

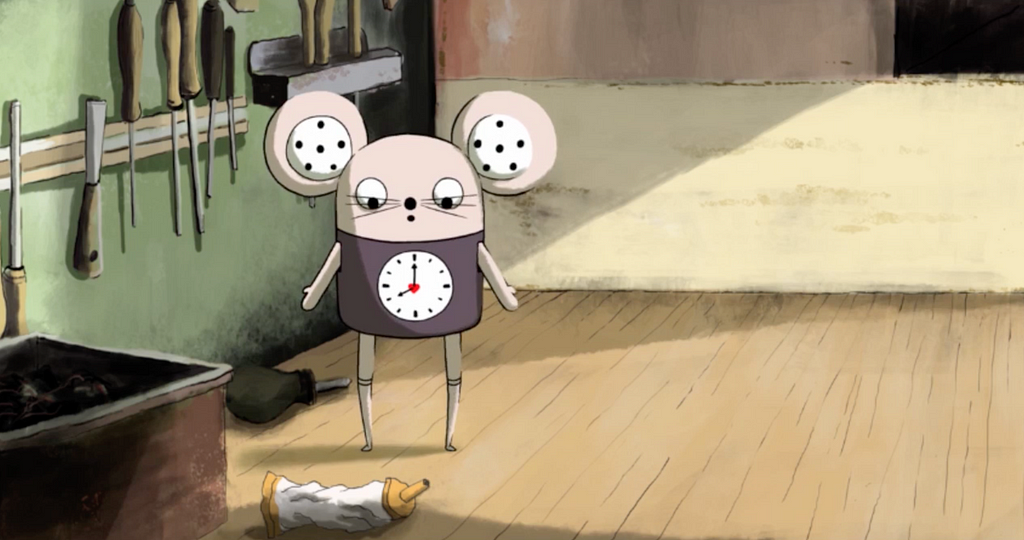

And yet, the animation itself is often presented as, for lack of a better word, cartoonish — including entire scenes and plotlines dedicated to goofy comedic bits and downright hilarious characters ranging from a talking alarm clock, an oppressed ducky raft, and a puppy that aspires to be engineer to please his controlling parents. And that’s hardly scratching the surface of the strange impulses that make Birdboy such an emotionally challenging work.

When Vázquez dwells on whether he was worried on how the film’s mixed tones would be received by audiences, he cracks a grin.

“We were very concerned that the story was very oppressive the entire time,” he says, laughing to himself, before explaining the film’s humor. “That’s why these moments exist—so the audience can relax a little bit. And there are also parts of the film that are a little more poetic and a little more self-reflecting. We were trying to bring a balance to it: an equilibrium.”

It would appear that this unique equilibrium has struck a chord with audience’s worldwide. In February of 2017, the film won the award for Best Animated Feature at the Spanish Academy Goya Awards, and has since been picked up by GKIDS for distribution. Birdboy has taken flight.

The film’s production was led by Vázquez in conjunction with Pedro Rivero — two Spanish directors with acclaimed backgrounds in animation, screenwriting, and illustration. The directors both have a quiet intensity about them, choosing their words carefully and speaking with a commanding confidence. When the Dot and Line sat down with the duo and their production team to discuss the film, it was in an uncomfortably hot and overlit Hollywood hotel room, yet each still took his time to thoroughly consider every question asked. It’s that meticulous attention to detail and dedication to the material that makes Birdboy such a compelling viewing.

Elaborating on the transformation of Birdboy from graphic novel to film, Rivero points to the the romance between Birdboy, the titular character and a shy, wordless drug addict, and Dinky, the story’s protagonist who dreams of getting away from her island home.

“In the graphic novel, there were a lot of stories within the island,” Rivero explains. “But the main plot line was the relationship between Birdboy and Dinky — just as in the graphic novel, it happened in the film. And when we decided to adapt [the graphic novel], we were actually able to get deeper into the story of Birdboy. And we amplified the story for the secondary characters. Nothing really new, but it could just be evolved.”

Rivero continues, explaining the film’s production process.

“As far as animation, we were a very small team—around 15 people,” he says. “We had to be very efficient in the moment of who was doing what and in deciding the workload. We had one animator who was very good at working the scenes with Mr. Clock, and we had another animator just working with the demons the entire time. It was finding their abilities that allowed us to really push our team forward.”

This balancing of roles presents itself in the film’s visual style above all else—especially in the balance between the dark and the light. At times, the screen is filled with lush imagery and smoothed, rounded lines. And moments later, horrific, jagged-looking creatures with brutally intense colors and movements take their place.

“The color is very important for this film because it’s symbolic and it expresses a lot,” Vázquez explains. “They are not natural colors, which helps to push further at the seams. Kind of like the nightmares where you have blacks and reds. It reminds you of German Expressionism, like Nosferatu. The backgrounds are very loose, and we wanted so you can see the actual sweep of the brush. We wanted to make it a style. I have an illustrator background and try to bring all that background from the books that I illustrated into it. I mean, the whole story [takes place] in one day. Sunrise to night.The colors reflect how day goes by. The strategy was not to repeat the chromatic schemes on each scene.”

But is the film’s depiction of such a terrifying world meant to be a reflection of how the two see the world as it is today, with all its faults?

“It’s a modern fairytale,” Rivero says. “We have a series of characters you can easily identify as teenagers, surrounded by troubles that are actually very contemporary. Pollution—the outside pollution that also bleeds into the interior of the characters. Addiction—the absence of people looking forward to a future in, especially within the youth, it can seem like a very dark point of view on the present. If you visit any of the world, a big city, that exists. Whether it’s L.A., in Brazil… or anywhere else. Especially for Alberto, it’s what motivated him, especially [considering] where he came from during the ‘80s.”

Rivero and the team behind laugh a bit before Vázquez happily opens up, as if not expecting to address a more personal subject.

“I’m from an area in Spain called Galicia, where, during the ‘80s, it was a gateway for cocaine and heroin,” he said. “It was right after the dictatorship and it was kind of an eye-opening moment. And the youth was taking drugs and they didn’t know the consequences of it. It did damage to the young population. That was one of the jumpstart points of the story.”

When asked what they want the audience to take away from the film, Rivero, still laughing, says that they hope the audience find some levity amidst all the chaos in the film.

“Yeah, we think there’s hope,” he says. “The example is that Birdboy leaves a cultural inheritance to Dinky [at the film’s end]. We needed it to be there. When we first talked about adapting the comic into a film, Alberto even mentioned that there was no hope left and that people were going to walk out of the film feeling horrible and crazy. In a very subtle but easy way, we left hope.”

Rivero laughs again. “We’re optimistic.”

That optimism can be found in some of the visual cues of the film, even when it seems buried by darkness. The characters, Vázquez says by way of example, could even be read as cute—something Rivero explicitly mentions as well.

“Telling stories with animals…it’s a tradition,” Vázquez says. “And it actually reminds us of childhood. You know, animals are cute, and the iconography is universal. They belong to the world itself, and it makes the film a more universal one.”

Unable to help himself, Rivero chimes in with a self-aware laugh.

“And it makes it more painful when you see them suffer,” he says. “Maybe there’s a little sadism to it, too.”

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.