What’s cool about mythopoeia is everything. What’s cool about cartoons is also everything. When cartoons take on ancient mythology and its fictional mythopoetic derivations, the results can be wondrous, disastrous, and sometimes both. Following is a cartoon mythopoeia and a tale of tales: five chronicles of five attempts to adapt epic, ancient, legendary sagas into animated feature films short enough to hold the attention span of a child. Or, like, me.

The Movie: Aladdin

The Source: One Thousand and One Nights

What’s the Connection: One Thousand and One Nights, often called Arabian Nights in English translations, collects Middle Eastern folktales from cultures across Asia and Northern Africa. It’s unknown when the compiled Nights first made its way into writing, but an Arabic manuscript fragment dates to the early 9th century. One Thousand and One Nights contains many characters that are household names even in the 21st century: Sinbad, Ali Baba, and, of course, Aladdin.

The tale of “Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp” follows a scrappy wastrel tricked by a sorcerer into entering a magical cave to retrieve a lamp. Once inside the cave, the sorcerer traps Aladdin underground. Aladdin is wearing a magical ring lent to him by the sorcerer, which he inadvertently rubs, and in doing so releases a jinn, or genie. The jinn of the ring helps Aladdin safely out of the cave and back to his mother, lamp in tow. When Aladdin’s mother tries to clean the lamp so they can sell it, she inadvertently releases a second jinn. The jinn of the lamp is more powerful than the jinn of the ring. With his help, Aladdin marries the sultan’s daughter, Badroulbadour, and gains power, riches, and a palace even fancier than the sultan’s.

Of course, the evil sorcerer hears about all this, and gets huffy. The sorcerer tricks Badroulbadour into letting him hold the lamp, then gets the jinn to transport Aladdin’s palace to the sorcerer’s home in the Maghreb. Fortunately, Aladdin still has the magic ring, and uses the first jinn’s help to transport him to the Maghreb as well. Aladdin and Badroulbadour hatch a plan, and Badroulbadour uses her seductive wiles on the sorcerer: “O my darling, do thou (and thou be willing) come to me this night and let us sup together… I have determined upon taking thee to friend and playfellow in lieu of and succession to Aladdin, for that now I have none other man but thyself. So I hope for thy presence this night that we may sup together, and we may carouse and drink somewhat of wine with each other.” Badroulbadour drugs the sorcerer, and Aladdin comes in, kills him, and takes his dang lamp back. Then the sorcerer’s brother tries to kill Aladdin and it’s this whole other thing, but Badroulbadour and Aladdin still come out on top.

Okay, okay, so now it’s 1992 and Disney decides to make their Aladdin. Some of the plot points stick: Aladdin is scrappy; a princess uses her feminine wiles to screw over a sorcerer; there is a magic lamp with a genie inside. Disney dropped the first jinn of the ring, changed Badroulbadour’s name to Jasmine, and added a pretty cool tiger, who I would in no way mind having as my animal companion.

The Movie: Arjun: The Warrior Prince

The Source: Mahabharata

What’s the Connection: The Mahabharata is unique among these legendary texts in that its canonical author is also one of its characters: Vyasa. Assisted by the god Ganesha, Vyasa narrated the entire Mahabharata without pause while Ganesha transcribed. (“Ganesha: ‘I will become the writer of thy work, provided my pen do not for a moment cease writing.’ And Vyasa said unto that divinity, ‘Wherever there be anything thou dost not comprehend, cease to continue writing.’”)

While the Mahabharata contains devotional and philosophical portions, its narrative lies in the conflict between the five Pandava brothers and their cousins, the Kaurava brothers. One of the Mahabharata’s central characters is the warrior Arjun, a Pandava. Although this epic poem depicts many battles and quests, one of the tales that really piqued my interest was Arjun’s marriage to the Princess Draupadi. When the Pandavas attend a Swayamvara—a ceremonial contest in which a woman chooses a husband from amongst many suitors—for Draupadi, only Arjun is able to fire an arrow into the eye of a goldfish by looking only at the fish’s reflection, thus winning the princess’ hand in marriage. When the Pandavas returned home, their mother, without looking, told Arjun to share whatever alms he’d brought back with his brothers. Arjun took his mother’s words as divine command, and thus, Draupadi married all five brothers. Her ancient polyandrous arrangements? As clarified by author Devdutt Pattanaik, “every brother has exclusive rights to Draupadi’s chambers for a year, and then has to wait for four years for the next turn…Before she moved to the next husband, Draupadi walks through fire to regain her virginity and purity. Such rules were never placed before polygamous husbands.”

In 2012, Disney and UTV, a Disney India subsidiary, released Arjun: The Warrior Prince, an animated feature about Arjun’s young life. We don’t ever see Vyasa or Ganesha writing. Instead, the film focuses on the battles between the cousins. The action sequences are beautifully choreographed; in one of my favorite scenes, Arjun takes a pterodactyl-looking demon by the neck and swings it like a lasso.

When Arjun wins Draupadi’s hand, they only show one other competitor failing to shoot an arrow into the goldfish’s eye. In the poem, many conflicts arise during the Swayamvara, before and after Arjun’s success—another king, for instance, attacks Arjun out of jealousy. Perhaps predictably, Draupadi doesn’t marry all five brothers in the film, but only Arjun. She certainly doesn’t walk through fire to “purify” herself between partners. Polyandry, I suppose, wouldn’t be up Walt Disney’s infamously patriarchal alley.

The Movie: The Black Cauldron

The Source: The Mabinogion / The Chronicles of Prydain

What’s the Connection: The Mabinogion is a collection of tales from early British mythology, compiled in Middle Welsh from the oral tradition during the 12th and 13th centuries. A lot of extremely cool heroic action happens in these tales, and here’s a particularly relevant bit: the Pair Dadeni (the Cauldron of Rebirth) is a cauldron with the capability of reviving the dead. When a battle breaks out between the Irish and the Welsh, the Irish begin using the Cauldron to revive their slain. Then, Welsh anti-hero Efnysien (kind of a dick, once described as “a study in the psychopathic personality”) does a heroic thing by hiding amongst the Irish corpses, getting himself thrown into the Cauldron, and destroying it from within.

Fast forward to the 1960s, when Lloyd Alexander wrote the Chronicles of Prydain, a children’s high fantasy series. (As a kid, I was obsessed with this ’90s cover.) The books take place in the mythical kingdom of Prydain, but the geography, themes, and certain characters take direct inspiration from Welsh mythology, in particular the Mabinogion. In the first two books, the heroes fight a slew of undead warriors who have been reborn in what is known as the Black Cauldron, which is functionally very similar to the Mabinogion’s Cauldron of Rebirth. Ultimately, annoying nobleman Ellidyr leaps into the cauldron, sacrificing himself to its destruction—more nobly, perhaps, than Efnysien, who didn’t sacrifice himself on purpose.

In 1985, Disney attempted to squish the five-volume series into one movie, The Black Cauldron. Through this wacky chain of inspiration, we arrive at the critically panned animated feature film that we all—well, some of us—know and love.

In the Mabinogion, the ruler of the underworld is named Arawn. The mythical Arawn is pretty chill: he’s married, enjoys hunting with his hounds, and gives gifts of magickal pigs to his buddies. In Lloyd Alexander’s books, Arawn Death-Lord is the big bad: he murders men to re-animate them as undead Cauldron-Born and incessantly terrorizes Prydain in attempts to become its supreme ruler.

Disney, however, decided their primary antagonist should be the Horned King—a minor villain in Alexander’s series, one of Arawn Death-Lord’s underlings. Why did Disney make this call? Because, according to story writer and producer Joe Hale, “we thought [the Horned King] would make a good animation character mainly because he had horns sticking out of his head.” Great, replace Wales’ legendary lord of the entire underworld with a dude who looks like Skeletor. Can’t imagine why this movie flopped. (I love it.)

The Movie: The Princess and the Goblin

The Source: Northwestern European folklore / The Princess and the Goblin

What’s the Connection: Goblins appear all across European mythologies. First written about in the 14th century, their behavior and appearance vary somewhat depending on each tale’s origin, but they tend to be diminutive, treasure-loving, and rather unpleasant to look at—unless you’re into that sort of thing, which is totally cool—and personally, if we’re talking about Jareth the Goblin King, well…. Anyway, under the umbrella of goblins, gobelins, goblings, goblyns, goblinos, et cetera, we find forms like kobolds, trasgos, lutins, and kallikantzaroi. Perhaps because these creatures vary in appearance and disposition, they’ve become staples of the fantasy genre, whether you’re playing D&D, watching horror movies, or reading 19th century poetry.

Scottish author George MacDonald is largely responsible for popularizing goblins in his 1872 children’s novel, The Princess and the Goblin. The story follows eight-year-old Princess Irene, who befriends a miner’s son and later rescues him from the clutches of cave-dwelling, poetry-hating goblins. Fantasy author Rohini Chowdhury writes that MacDonald “probably based his goblins on the Dark Elves of the Icelandic Eddas, the 13th-century collection of poems and stories that are our main source of Norse mythology.” This tracks in terms of housing preferences, as both the Dökkálfar (dark elves) and MacDonald’s goblins live subterranean lifestyles. (D&D took…a different route with dark elves, to say the least).

MacDonald’s book has been adapted often: for television by Shirley Temple in 1961, for the ballet by Twyla Tharp in 2012, and for film by director József Gémes in 1990. The film was a Welsh, Japanese, U.S., and Hungarian production—in fact, it was Wales’s first animated feature—and it flopped fantastically in the United States. One scathing review pointed to The Princess and the Goblin’s “unresolved story points and stiff animation”; the New York Times called the cinematic goblins “ineffectual and unmenacing even when they are on the warpath.”

Like The Black Cauldron, The Princess and the Goblin suffers from lack of attention to its source material, circumstances rather to the opposite of the books’ respective successes, especially considering that Lloyd Alexander cited MacDonald as an influence. The Princess film uses certain details of MacDonald’s story, and then seemingly forgets to point out their relevance. For example, the goblins’ soft feet are their primary weakness. In the film, the miner’s son realizes that the goblin queen has six toes, while all other goblins have only one. This is… never mentioned again. (It’s important because, due to the embarrassment of having toes, the queen wears shoes, which also serve to armor her weak points.)

As Princess Irene’s nurse helpfully notes, “strange things…you never know when they might happen.” This film is a bizarre relic of the ’90s via Victorian literature via Northwestern European folklore. I only wish it had paid a little more attention to detail. I…still love it.

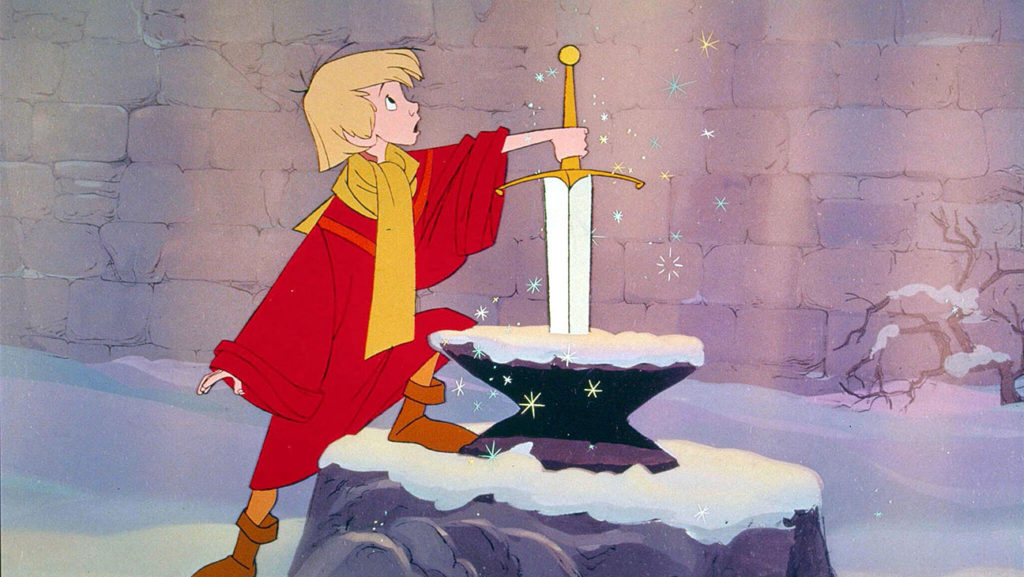

The Movie: The Sword in the Stone

The Source: Le Morte d’Arthur / The Once and Future King

What’s the Connection: Le Morte d’Arthur is a 15th century collection of legendary tales—a work of pseudohistorical historiography here, some chivalric romances there—about King Arthur and his knights, collected and rewritten by Sir Thomas Mallory. “The Hoole Book of Kyng Arthur and of His Noble Knyghtes of the Rounde Table” was the original title Mallory wanted, and you know what? First thought, best thought, if you ask me.

You probably know the basics of Arthurian legend: a boy pulls a sword out of a rock, which means that he’s the next King of England; he becomes king, lives in Camelot, leads the Knights of the Round Table, and marries Guinevere; oh and also he unwittingly had sex with his sorceress half-sister one time and she gave birth to a boy who would become his nemesis. Classic stories all, leading to fine animated features like Quest for Camelot The Sword in the Stone.

In 1938, T.H. White published a chronicle of Arthur’s boyhood derived from Mallory’s texts, called The Sword in the Stone. Later, this novel was revised and compiled into White’s much-adapted 1958 tetralogy, The Once and Future King.

In 1963, Disney adapted The Sword in the Stone into a musical comedy featuring Arthur, Merlin, and my all-time favorite animated witch, Madam Mim. (“Black sorcery is my cup of tea!” So relatable.) The film sticks pretty closely to White’s narrative, making the same updates from Mallory’s text: Arthur is Anglo-Norman rather than a Celtic Briton; the story takes place in the 13th century (a scant two centuries before Le Morte d’Arthur’s publication), rather than the 6th (when Arthur, if he existed, would likely have lived, not that Le Morte d’Arthur ever specifies a time frame or pays much attention to historical detail).

Merlin and Madam Mim’s battle happens in White’s Sword and the Stone, but was edited out for The Once and Future King—an outrage. Fortunately, the Disney movie cleaves neatly to its elder source material and shows Merlin and Madam Mim’s battle on-screen. I’d watch a Hoole Movie about that.

Top image credit: Collage of a screenshot of Disney’s The Sword in the Stone and scans of the British Library’s manuscript of The Legend of King Arthur (1469) by Sir Thomas Malory and its illustrated copy of Idylls of the King (1859-1885) by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.