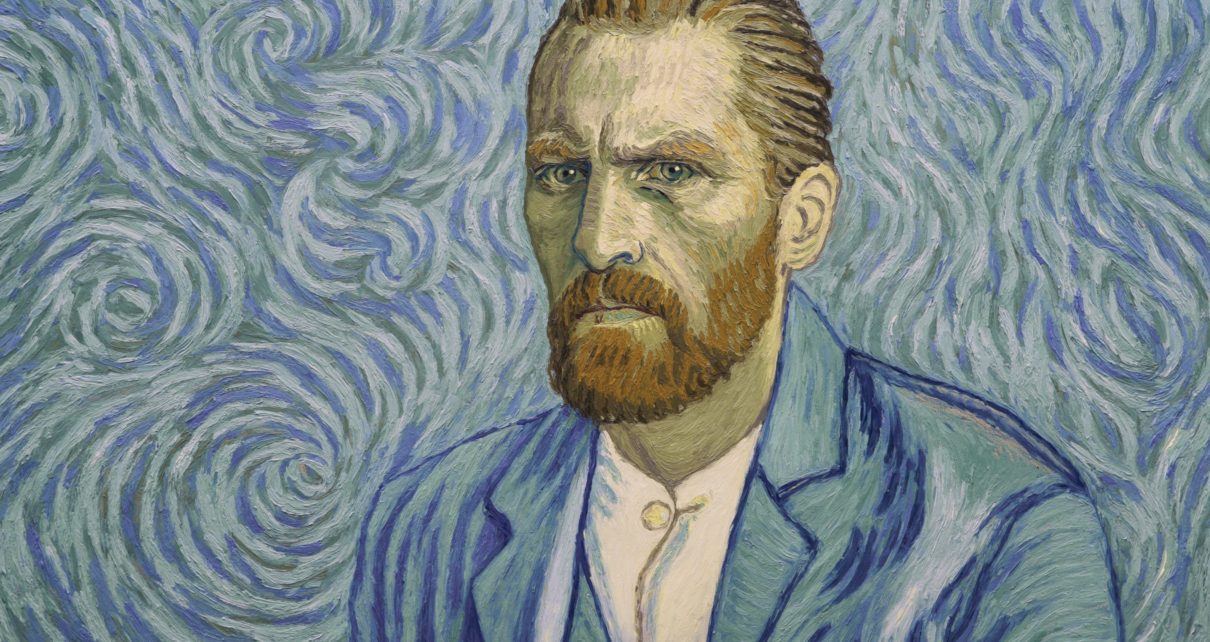

It would be redundant to call Loving Vincent—a poetic cinematic meditation on the life of Vincent Van Gogh wrapped in a whodunnit set a year after the great painter’s death by suicide—a labor of love. For one, there’s the title. For another, there’s the fact that each of the 94-minute film’s 65,000 frames is a single oil painting, hand-painted by one of 125 professional oil painters, each of which was rotoscoped, i.e., painted over one of the 65,000 frames of live-action film initially shot with the actors who play the film’s painted characters (like the old Disney films used to do)—which are, themselves, direct corollaries to characters from Van Gogh paintings and designed based on those paintings and also their respective actor’s IRL appearances. Yeah. They went in.

As such, it seemed right and just that we also go in. To a theater. To watch it. And to do so with appropriate fervor, we enlisted two of our most obsessive editorial staffers: editor John Maher, whose noted fever for animation and complicated feelings toward live-action have been well documented on this site, and Ask Scratchy columnist Amelia Kidd, whose passion for the Dutchman’s paintings nearly reaches the heights of her dedication to psychology and mental health. She bought the tickets. He snuck in some French cookies consistent with the period. It was cute.

Here is the full transcript of their consequent excited GChat discussion, lightly edited.

John Maher: Vincent Van Gogh once famously said, “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.” As a writer, I’ve often felt like my mind was already gone when I decided to put my heart and soul into that work, so I wasn’t entirely on his page — or, uh, painting?

Then I watched this movie. And I get it. I hope the animators are still sane.

Amelia Kidd: I’m not a painter, but I think some folks are relaxed by the kind of meticulous, repetitive work necessary for animation. Everything in this film was in constant motion. The leaves on the trees, the grass, the people and their clothing were always moving. I think the team of artists who made this film did that intentionally.

I took a class on modern art in my sophomore year of college. I remember my professor saying that Van Gogh painted Starry Night looking out of the window in his room at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, the asylum (or, in present-day medical speech, the residential mental health treatment facility) he stayed in after he cut his ear off, and that the dancing, swirling light may have been a direct depiction of how Van Gogh saw the world around him.

John: So, then, your thinking is that the constant motion of the many pieces of the film — the movements even of the painted lines of each character’s skin, let alone their bodies’ movements, and the movements of their clothing, and of their surroundings, and so on, ad almost infinitum — was supposed to be, in a way, a replication of his state of mind? Even though, in the movie, he was dead, and part of the plot only in flashbacks?

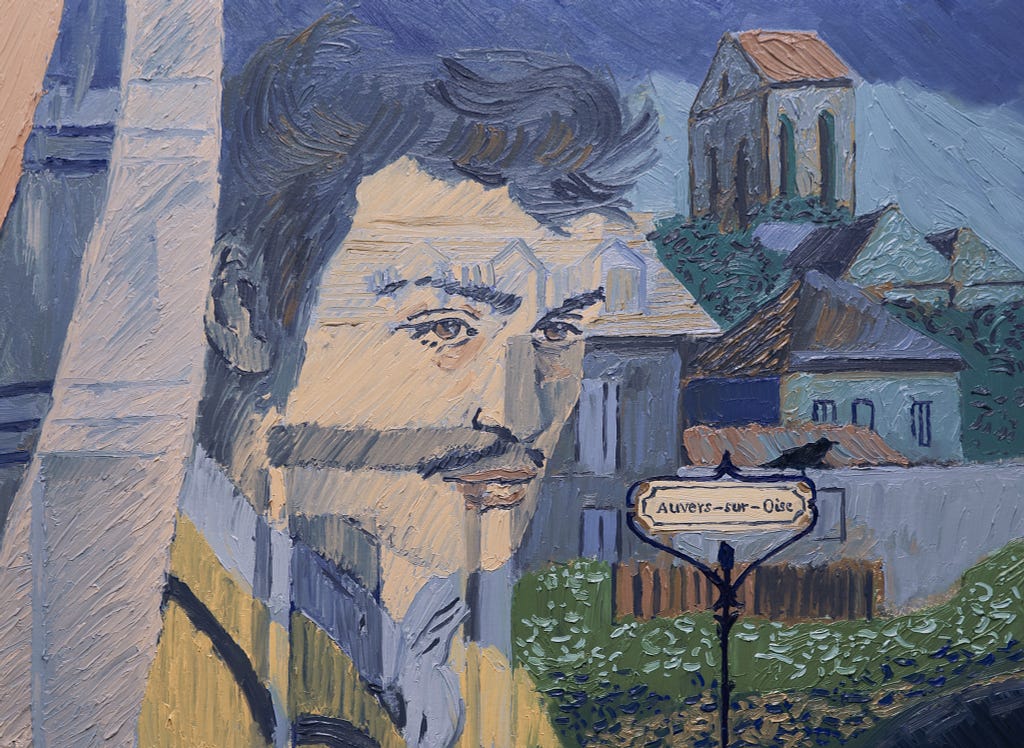

Speaking of which, I think it’s important to mention here that the art was staggering. So, the film takes places after Van Gogh’s death, and it’s told in two main visual palettes — a Van Gogh-esque, colorful one for the “present,” which is taking place a year after his death, and a smudgy but almost photo-realistic bIack-and-white flashback mode. The latter, honestly, I preferred, partially because it felt less aggressively like the film was yelling “look at us being Van Gogh!” and partially because I felt it did with shadow something the best noirs do while also finding a way to be a more oblique tribute to the master’s art. While the more colorful stuff felt somewhat distracting at times, especially in the beginning, when I wasn’t as used to its disjointedness.

Amelia: Yes, agreed. The uncanny valley doesn’t just apply to CGI. I learned that it also applies to animated oil paintings. But I’m not terribly surprised that the first-ever oil paint animation was about and largely in the style of Van Gogh. He’s arguably the most well-known painter in the Western art canon. Depictions of his life and his art are scattered across popular culture. (My personal favorite is during the Matt Smith era of Doctor Who.)

At the same time, I think this speaks to Van Gogh’s understanding of the human condition. This film (and other depictions) present Van Gogh as the ultimate empath.

John: More than… Michelangelo? Or da Vinci? Really? Anyway, that’s beside the point. It doesn’t entirely surprise me either. And while main visual style is pretty disconcerting, and sometimes inconsistent, it’s pretty objectively fascinating, and eventually you get used to it. Plus, I mean, you get to watch Van Gogh’s paintings come to life for 94 minutes—and watch them become characters in the plot of his life. It’s a pretty phenomenal feat.

What did surprise me, though, was the narrative technique. We’ve talked a bit—during our occasional “what should we watch tonight” conversations that usually involve “anything but a depressing black-and-white movie with subtitles, especially ones with samurai, please”—about how Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon basically invented an entire narrative technique in film that no one had ever done before: subjectivity and unreliability. One of the aspects of narrative storytelling that film, in its nascent days, offered in a way no other form did is a sort of objective reality even Tolstoy couldn’t nail. I mean, it’s…on film! What happened is there.

Then comes Kurosawa with a film examining a murder and probable rape recounted from four different perspectives, none of which are trustworthy. It gives us a look into the psychologies and subjective failures in perception of all these different characters and leaves us knowing as much as we did when we came in about the motivations and mechanics behind the act. It’s remarkable stuff.

This movie…basically does that, but with art! It asks if, maybe, the circumstances behind Van Gogh’s death are different from the story of a suicide we knew going in. And at the end, well, it’s been complicated, but our understanding of the end result hasn’t really grown. Instead, we’ve been moved, stunned, forced into a state of emotional overflow, and asked to sit with the idea that the facts around this man’s life and death may be somewhat inseparable from the myths and inconsistencies in the retelling of both.

Amelia: Yes! The main character, [Name], searches for the objective in the subjective. It reminds me of an epic tale some of you might be familiar with: A Song of Ice and Fire. My main man, George R.R. Martin, has an uncanny ability to enter into other people’s minds, to the point where (if we ever get there) we will never truly know how each character’s story ends. But I digress. The plot structure, although evidently used to great effect in other films, is fine. It serves its purpose.

So what’s really remarkable about this film then?

John: What, besides the stupefyingly gorgeous art, and the clearly insane amount of effort put into making that art happen, and the excellent voice acting that’s so good it saves the bits of a pretty good script that wouldn’t otherwise land, and the great cast that includes weird British standards singer turned weirdly hot George R.R. Martin minor character Jerome Flynn as Vincent’s homeopathic physician, Dr. Paul Gachet?

Well, in spite of the fact that you didn’t register his name—we’re leaving that in the piece, by the way—I was actually really impressed that Douglas Booth’s Armand Roulin, the protagonist (and actual Van Gogh subject), was initially a fiery-tempered, yellow-coated fuccboi about whom the audience really had no reason to care, yet ended up developing enough over the course of the film that he became a mostly likable character with understandable motivations and not just a vehicle allowing the directors to stroke their Van Gogh obsession. It helps that he started mostly as a cipher, but still, I think that’s something of a feat!

Amelia: Eh, I don’t know. I preferred his father, Joseph Roulin—played by Chris O’Dowd—a.k.a. the Dosteyvsky of the South, or whatever Van Gogh called him. Armand was a sympathetic plot device: a way to explore and complicate Van Gogh’s final years with as little bias as possible.

Which is problematic in and of itself. Much like Scott McCloud argues in Understanding Comics, young, reasonably attractive white males like Superman are objects onto which wide swaths of the population project their own conceptions of themselves. Unfortunately, the comics industry (and Western art canon) forgets that the vast majority of the people who make up the world are…not white men.

Speaking of which, Marguerite Gachet — Doctor Gachet’s daughter and Vincent’s rumored last love interest —cuts right to the quick in calling bullshit on Armand Roulin’s manic pixie dream painter journey.

John: Yeah, this is all true—although we are talking about events set in 19th-century rural France, so the unbearable whiteness of being there was pretty unavoidable.

Either way, I found myself…surprisingly moved by the film. The Roulins were frequent Van Gogh subjects, and there was something about seeing his perceptions of them—his paintings of them—come to life in their attempts to understand him, in conjunction with other Van Gogh painting-persons, after his death that felt particularly emotionally profound.

Which brings us, I suppose, to the film’s ending scene, in which Armand reads to himself the final letter from Vincent Van Gogh to his brother, Theo. The “loving” in the title comes from Van Gogh’s epistolary sign-off: “Your loving Vincent.” The artist once said, “Love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is done well.”

If anything, Van Gogh loved too much, and lost himself in the painfully huge sweep of that love. And yet, as Roulin’s voice turns to Van Gogh’s as he reads the letter, the film pans up into that famous night sky—echoing another set of Van Gogh’s famous words: For my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream.

Us too.

*Disclosure: The writers of this article regularly smooch, sleep in each other’s beds, and cuddle together with their respective cats and/or stuffed animals.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.