Truly remarkable animation can reflect the best and worst aspects of being human back to us as no other form of film can. Tales From Earthsea, while not the most beloved of the films produced by Studio Ghibli, is no exception. The film occupies a territory many other animated features only touch upon tangentially — that is, its characters are more than cartoon figures, operating as knotty, wholly relatable reflections of the complexities of the human condition.

Director Goro Miyazaki’s Earthsea was adapted from the young adult sci-fi series of the same name written by the late Ursula K. Le Guin, a titan of late 20th Century speculative literature (and literature in general). Like Le Guin’s series, the film follows the trials and tribulations of a young prince named Arren, who kills his father on a sudden, unexplainable impulse and afterward flees his kingdom. Soon, he is surrounded by a pack of wolves but, before being ripped apart, he is rescued by the sorcerer Sparrowhawk. Thus begins their adventure together, during which the gentle and gracious Sparrowhawk becomes Arren’s mentor, teaching him about the light and dark forces in the world that disrupt its balance.

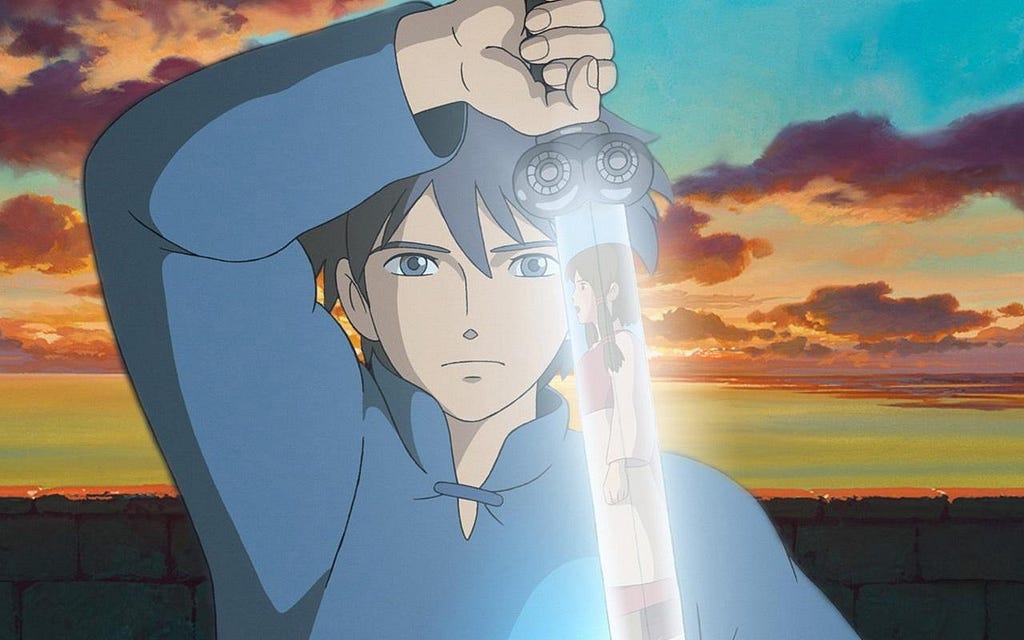

The film’s style boasts many of the trademarks of the works of Goro’s father, Hayao Miyazaki, and is filled with bright and beautiful color schemes that make for a stark contrast to the many serious and introspective topics that Earthsea explores. While both the book and Studio Ghibli adaptation are meant to serve as an allegory for the consequences of human arrogance (particularly global warming), what the movie does best is speak to the hellish void that must be overcome when facing one’s own inner fears and faults — a tricky feat for any film.

In an essay Le Guin penned in response to Ghibli’s Earthsea adaptation years ago, the author detailed her rebuffing of Hayao Miyazaki’s initial request for her permission to adapt an animated film from her book almost three decades ago. Le Guin wrote that she knew “only Disney-type animation” and disliked it, and so turned Miyazaki down. Much later, when a friend convinced her to watch the classic Miyazaki film My Neighbor Totoro, she loved it so much that she became a life-long Miyazaki fan, dubbing him “a genius of the same caliber as Kurosawa or Fellini.” Her opinion of Goro Miyazaki, in contrast, is less kind — especially because much of the plot for the anime adaptation was taken from the Miyazaki manga The Journey of Shuna, and did not reflect Le Guin’s original plot or purpose.

Le Guin details her frustration with the film in her response, explaining why she was disappointed in the differences between the animation and her books, saying, “The moral sense of the books becomes confused in the film.” In her argument, she cites that Arren’s murder of his father in the film appears “unmotivated” and “arbitrary” until the end when we understand he was being controlled by an evil spirit.

Le Guin’s disappointment stems from her knowledge that “the darkness within us can’t be done away with by swinging a magic sword” and that the film attempts to, in her words, show evil as “comfortably externalized in a villain […] who can simply be killed, thus solving all problems.” The author summarized her feelings by explaining that her books can “offer no simple answers to simplistic questions,” which she felt the animated version of her Earthsea saga ultimately attempted to do.

While the plot in Miyazaki’s adaptation does stray from Le Guin’s original Earthsea novels, and her criticisms of its offering of a more “simple” narrative about evil are valid, I still couldn’t help but feel the same kind of thrilling unease and bout of self-questioning after watching the movie as I did when I first read the Earthsea books as a child. It struck me that while there are many differences between the ways that evil is portrayed untangled in novels and how it’s done in movies, the animated Earthsea shares something incredibly important with its counterpart — the nuance and honesty with which it holds a mirror up to its audience.

The dark parts of the film, however simplistic, still explore the basics of human nature, evil, and impulse in a way that communicates how natural these feelings and struggles are. And most of the film still revolves around Arren’s attempt to overcome dark inner leanings that he doesn’t understand and whose source he cannot seem to discover — an attempt he occasionally runs away from, as we all often do from our own troubles.

Early on in the movie, for instance, Arren runs into a man who offers him a supplement called “hazia,” which, he is promised, will take away all of his sorrow and fear, leaving him to never again be forced to deal with the “misery and suffering of this world.” For a brief moment, terrified of the uncertainty of the future, Arren considers taking the quick fix before he’s once again rescued by Sparrowhawk. That kind of drug is not “something to flirt with,” Sparrowhawk tells him — while it may not be easily noticed, danger lurks taking the easy ways out of life’s pains, whether small or large. Arren’s anxieties about his life are seen and felt so clearly here, and his temptation to escape his problems with a “happy pill” is a familiar one. How many of us have been persuaded to have one too many drinks after a rough week, or have found ourselves turning to other questionable coping methods?

Similarly, Arren’s whole journey is marked by the rawness of his struggles. At one point, Arren is confronted by a ghostlike stranger who is almost the spitting image of him — clearly meant to represent his “dark side” and the worst version of himself. He runs away in fear, stumbling into a small lake and nearly drowning. And who couldn’t identify with that? One of the best parts of reading a book is finding a character you feel connected to, whose internal struggle you can see and understand and, suddenly, you don’t feel so alone. Although the animated Arren’s “inner darkness” is ultimately defeated because it only existed due to outside evil forces, the journey of angst and self-discovery in the film is still extremely relatable.

Because of this, Le Guin’s original prejudice — the idea that animation cannot be serious, or cannot truly capture the full complexity of humanity — fascinates me. Many share this view, refusing to take anything animated seriously, and citing outdated examples from the medium to insist that “cartoons are just for kids.” But if animation can’t capture the complexity of the human experience, how can I relate so well to cartoon characters that, by all measures, could not be said to have lived a life the way I have?

Miyazaki’s Arren, for all his faults, is still an eerily accurate depiction of anxiety, and I find it hard not to be convinced, after witnessing him, that cartoons are more than capable of telling even the most complex stories. What Earthsea truly gets right, as many other Studio Ghibli films such as Kiki’s Delivery Service or My Neighbor Totoro do, is capturing the journey that inevitably follows in the wake of grief — one that provides an often jagged road to growth. That this jaggedness showed in Tales from Earthsea isn’t a weakness — it’s a strength.

And with its characters’ complexity and sheer humanity, the animated version of Earthsea shows that animation is capable of telling these stories just as well as a live action cast could.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.