Eds. note: The following is an adapted excerpt of COOL: Style, Sound, and Subversion by Greg Foley and Andrew Luecke, a bible of fashion, history, and analysis of subculture and adornment throughout the ages. The Dot and Line is publishing this adapted essay with permission. Definitely buy a copy.

Believe it or not, before the 1980s, the Japanese word otaku was simply an honorific pronoun meaning “you.” But by the start of that decade, shy anime and manga fans began using otaku to refer to one another at comic conventions and shops when their social unease prevented them from using more casual, intimate pronouns.

The term has retained its self-conscious, socially awkward connotations ever since. But not without a huge boost from Akio Nakamori, an editor at lolicon hentai rag Manga Burikko. In a 1983 column, he amplified otaku’s colloquial usage, applying it to the shy, difficult fans who were obsessed with Manga Burikko’s explicit comics featuring sexualized prepubescent girls. Sure, Japan tolerates such media, but it seems that even for a columnist at such a magazine, devoting oneself to lolicon at the exclusion of success in school, family, career, or actual dating warranted calling out. Things only got worse for otaku when Japanese media labeled nerdy serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki “The Otaku Murderer” after he dispatched four young girls between 1988 and 1989.

But things didn’t stay all bad for the otaku. And now, most people likely recognize otaku culture by its sanitized, Western iterations, reclaimed by Japanophile nerds to tout their devotion to anime, manga, and all things geek. Indeed, since “The Otaku Murderer” nadir, the term is less offensive in Japan than it once was. And there’s one very important reason for this transformation: anime.

Nakamori’s coinage of otaku coincided with the great anime gold rush of the 1980s, when iconic shows like Robotech (1982–1984), Mobile Suit Gundam (1979–1980), and Bubblegum Crisis (1987–1991) were exploding in Japan and even taking anime’s stylized, laser-hot freneticism worldwide. And epochal films like 1988’s Akira only added to the ferver. Soon, anime was even going for self-referential laughs, spoofing otaku culture in classic comedies like Otaku no Video, a twist that still pop ups in films and TV shows to this day.

Arguably, anime only got better and better during the 1990s, as masterpieces like Ghost in the Shell (1995), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–1996), and Princess Mononoke (1997) streamed out of studios, showing up on the air and in movie theaters across Europe, the United States, and South America.

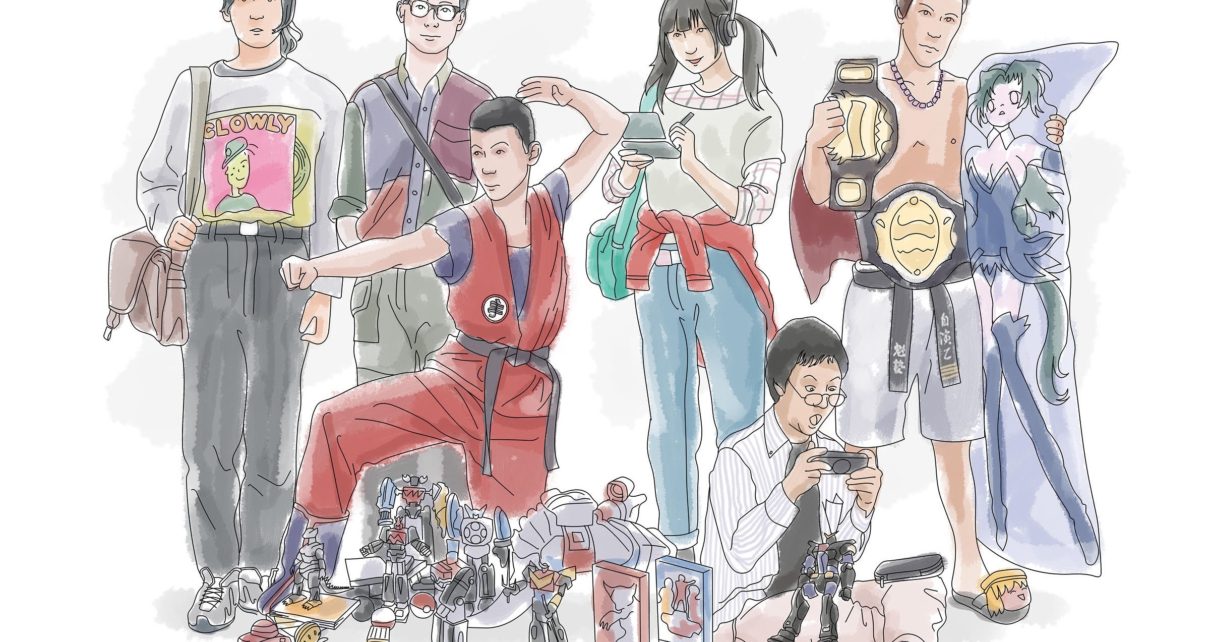

And just as anime expanded during the 1990s, so did otaku culture, both in scope and global reach. In Japan, otaku-hood became specialized, with adherents devoted to all manner of nerdom and obscura. Now there were giant robot otaku, cosplay otaku, J-pop otaku, and even otaku devoted to military obsessions and train spotting. Some Japanese fanboys, lonely and obsessed, even chose to “marry” their favorite dakimakura body pillows, which bore images of fetchingly artificial bishōjo (beautiful young girls) from their favorite anime. Even so, the otaku ranks only swelled, eventually attracting women to the geeky fold, though nobody seemed be getting laid as a result.

In turn, anime fans and geeks around the world responded to the diversification of otaku culture, embracing its trappings all the more for its variety, which allowed them to see even more of themselves reflected in this strange, socially-isolated Japanese nerdom. By the turn of the millennium, shows like the clever, philosophical Cowboy Bebop (1997–1998) had proven that no matter where it landed outside of Japan, anime — and its attendant otaku culture — was no mere fad, but a permanent, vital part of the cultural lexicon. Back in Japan, the once derided otaku were even influencing cool kid fashion, having cultivated a devotion to Nike Dunks that allegedly caught the eye of the streetwear kings at Supreme. By 2002, Supreme partnered with a nascent Nike SB to revive the then forgotten ’80s basketball shoe, turning it into a coveted paragon of hipness that could resell for over $1,000.

All the while, the anime hits just kept coming. With releases like the strange, ethereal Paprika (2006) and nearly universal Internet access, anime fandom became further entrenched in Western culture, which only helped to lessen the otaku stigma in Japan. In 2007, Sovereign Media published the first issue of Otaku USA magazine, a fitting testament to mainstream acceptance that bookended nicely with otaku’s cultural origins in a trashy lolicon mag. And otaku everywhere — from Tokyo to Rio de Janeiro to Brooklyn — owe this transformation completely to anime, with its amazing artistry, scope, and downright coolness. All of which easily captured the hearts of millions.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.