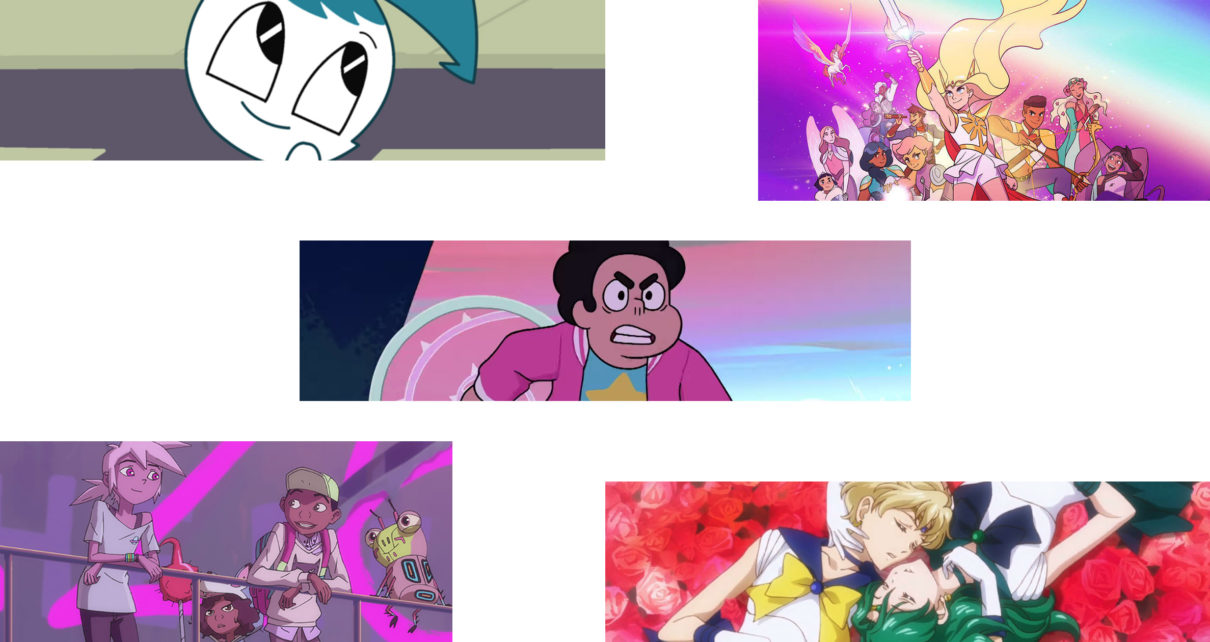

In recent years, Steven Universe has been heralded as the boldest of queer cartoons, bringing marginalized identity to the forefront and finding new, nuanced ways to reckon with things like queerness and trauma out in the open. But while Rebecca Sugar’s masterpiece may be upheld as one of the brightest queer stars to shine in the world of animation in recent years, there were many cartoons with queer storylines, however subtle or packed under subtext as they might have been, that came before it, like The Legend of Korra and its subtle romance between Asami and Korra. And there will be cartoons that continue to carry the torch long after it. The question is whether future cartoons will continue to do queer people in the outside world justice or not.

Shows like Netflix’s She-Ra: Princesses of Power have taken old tropes loaded with queer subtext and brought them into the light, banishing the subtext to the darkness. The reboot of She-Ra has blatant queer text, with multiple openly confirmed queer princesses, two gay dads, and an explicitly nonbinary character.

In Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts, queerness is also normalized. Early on, viewers find out one of the main characters is gay because another ends up having a crush on him. He turns her down politely, simply saying, “I’m gay.” It was hearing a character on a kids show say those two words so simply and clearly, without problem or shame, that feels so powerful for queer adults who grew up desperate for any representation, even if it was subtextual, Cas, a queer parent, explained to me. “I want the world to be better for my kids than it was for me growing up,” they say.

For Cas, Sailor Moon was the first cartoon in which they saw subtextually queer characters, and it changed their life. “I grew up pretty sheltered,” they say. “I didn’t know LGBT people existed until my teens, when I found out for myself through the wonders of the internet and a friend at school with a gay mom. Being able to read about queer characters helped me feel less like there was something wrong with me.”

The cartoons that have emerged in the last five years or so are much different from shows like My Life As a Teenage Robot, which fans have noted serves as a coded metaphor for the experiences of a queer or transgender teenager, whether intentionally or not. Or like Scooby-Doo: Where Are You?, in which Velma and Daphne maybe had some chemistry going. Those cartoons had hints of queerness, like a cake with the faint memory of lemon baked in, instead of a lemon cake itself, where the citrus is front and center, and you can tell that it’s supposed to be.

“I started noticing this pattern in ensemble cartoons where the girls fall into broad categories: cuties, tomboys, and gross girls,” says Kate Browne, a queer writer and television scholar. “Growing up in the 80s & 90s as a fat girl, I knew I wasn’t a cutie like Sally from Peanuts or Brittany from Alvin & the Chipmunks or She-Ra. I felt more like a tomboy—Francine from Arthur, Spinelli from Recess, Skeeter from Muppet Babies, Daria and Jane in Daria—but none of those characters were coded as fat. The only time I ever saw fat girls in cartoons, which was rare anyway, they were some combination of gross, loud, mean, awkward, and gluttonous: Eleanor from Alvin, Helga from The Oblongs, Grenda from Gravity Falls, Lumpy Space Princess from Adventure Time. These girls are never on the desired side of a crush—in fact, they are often sexually aggressive—and the humor always came from their humiliation.”

Browne, like many others, wants to see fat and diverse, desirable queer characters who are loved for their supposed “flaws” and differences, not brushed aside as material for a laugh. “It might sound like the focus here is on body size, but I didn’t realize until I was 35 years old that I couldn’t see myself in the queer-coded characters I admired,” Browne says. “The masc-of-center girls I admired were strong and honorable and successful…but they didn’t look like me. It’s like my fatness undercut any chance I had to see myself as a ‘good’ tomboy, putting myself in the category of the gross girl. I think this had a profound impact on the development of my sexuality and gender expression, contributing to my coming out as queer last year at 35.”

For Debbie Ojeda-Leitner, a psychologist and queer health policy expert, “to hear cartoons talk about who their general [medical] provider is, how trauma can have an impact on our physical health, and how to practice mindfulness” was to simply be blown away by just how far the medium has come in terms of representation. “Steven Universe helped me accept who I am as non-binary—I only came out just three years ago, and I am now 32,” they say. For Ojeda-Leitner, the earliest representations of queerness in cartoons with which they were familiar also came from Sailor Moon, as well as Daria. Still, most of this was underlying and less forthright than in shows like Steven Universe, which put identity front and center in tangible ways, like by having multiple queer characters in relationships, such as the essentially lesbian couple Garnet.

Queer fans of cartoons who spoke with me explained that they hope that animation will continue to be as intentional as possible about who their LGBTQIA+ characters are in the future. “It isn’t just about having characters that are queer, but also giving kids the opportunity to critically think about difficult conversations like physical and mental health, discrimination, and every day struggles that we may face, so I hope that continues,” says Ojeda-Leitner.

“We need cartoons, and I would argue other forms of entertainment that are more intentional than just having inclusivity and diversity,” they add. “We need stories that have major implications in our own lives and allow us to feel that our unique experiences with this wild world really do matter—especially these days, in which life is becoming more unpredictable and difficult. I hope to see that more in cartoons.”

So how exactly do queer people who love cartoons, no matter their age, want to see queerness better and more thoughtfully represented in cartoons in the future? “I want to see textual trans girls, especially those who have female love interests,” says Serenity Dee, a transgender woman. “To me, Perfuma from She-Ra reads as a trans girl, not just because of her tall, lanky build, but because of her enthusiastically whimsical, ebullient personality, which feels so much like how a lot of us trans women present once we’re able to fully be ourselves. But it’s not text, and I’d love to see her confirmed as trans in the same way that I’d love to see Bow confirmed as trans. (There’s been a fan theory about him since the first season.)”

Liz Gresser, like many others I spoke with, wants to see more cartoons with queer kids navigating the world with queer friends. “I love She-Ra and Steven Universe, but it seems like the queer characters are all teenagers and older. I want to see queer kids crushing on each other,” she says, adding: “I think I would have come to terms with my queer identity sooner if I would have been able to name certain feelings as a crush. Instead of pretending I had a crush on some random boy, I would have been able to recognize my feelings for girls weren’t just friendship feelings, because I had seen it on TV.”

For Gresser, cartoons with fantastical elements provide an excellent escape, but sometimes, queer people just want to see more slice-of-life entertainment. “I would love to see a show like Arthur with a cast of queer kids. Monsters and fantastical creatures have often been queer-coded, so I think in order to normalize queerness in cartoons, we have to see human queer characters,” says Gresser. Most of the queer people I spoke with didn’t want cartoons necessarily about queer people and their queerness, but to see queer people going on adventures that are not dedicated to origin stories but simply to their stories—stories that also happen to be about queer people.

“Ultimately, I want LGBT representation to be so commonplace that we don’t need articles like the one you’re writing,” Cas says. “I don’t want creators to have to fight just to show queer characters doing what straight, cis characters have always been able to do without any question. I want every kid, no matter where they fall on gender/orientation spectrums, to see characters like themselves.”

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we’ve written about animation of all kinds for more than four years. We’ll miss you! If you’ll miss us too, show us some love on Twitter and show our writers the money on GoFundMe. Read our goodbyes here: That’s All, Folks!

The part about the three ‘girl character’ archetypes really hit home. It reminded me of the weird emotional cocktail of gratefulness, delight, discomfort and irritation I felt when I first watched the one Gravity Falls episode in which another character does show a romantic interest in Grenda — but it’s still portrayed as the punchline to a B-plot joke. As I wrote in my first ever article for D&L, Gravity Falls can sometimes be a cruel animation.

Thank you for writing this, Elly, it’s an excellent round-up of the strides in representation cartoons have made in recent years — although of course there’s plenty to aspire to in the future.