It published scores of stories on Chuck Jones and Rebecca Sugar and Hayao Miyazaki and Shinichirō Watanabe and the rest because they were there, and on nearly every other cartoon it could because those cartoons were also there.

It published long features and punchy blogs and recurring newsletters and deep interviews and absurd jokes and extended gags and actual poems and arduous, multi–part packages, because those, too, were there, waiting to be shepherded into the glowing light of computer screens worldwide.

Its editors stayed up working far too late far too often, because the night, too, was there, and because even though, by day, they worked at jobs that paid them real (if far too few) American dollars, the lure of watching animation of all kinds, and of writing that explained and reflected its artistry, proved irresistible.

In early 2016, after reckoning that too little of the great writing that exists on the internet had nearly enough to do with their preferred art form, journalists John Maher and Eric Vilas-Boas created The Dot and Line, a website of animation journalism. It began with the duo alternating stories on a weekly basis before taking on contributors and, over the course of 2017 and 2018, adding three collaborators to its editorial team: Elly Belle, Marley Crusch, and Sammy Nickalls.

All work on the site was accomplished in a volunteer capacity and is reflective of the largesse its contributors and editors brought to the project. The site never earned a cent of revenue, but its ambitions never wavered, and it went on to publish more than 100 contributors in its short lifespan thanks to the occasionally unhinged tenacity of its editors and the unflagging goodwill of its contributors.

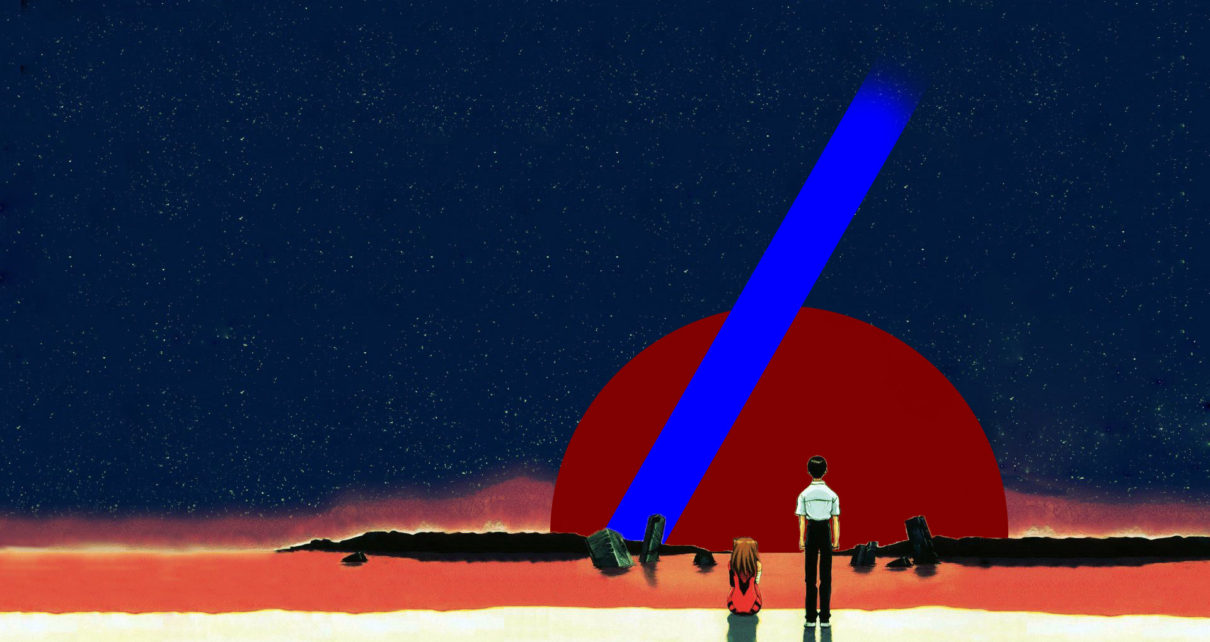

Over the course of four years, the site grew from a scrappy, puckish up-and-comer to quite possibly the finest cartoon journalism publication in the known universe. Its voice was breezy, but considered, its focus specific but its purview broad. At any given time, a reader may navigate to its homepage and find a 5,000-word personal essay about emotional trauma nestled into a close analysis of Cowboy Bebop next to a list of mice and rats in cartoons, ranked.

Diversity among both its contributors and content was a longstanding priority for the site’s editorial team, which endeavored to create a place on the internet for both amateur and expert writers to publish professionally edited work each week. Animation as a topic of coverage, the site’s editors went to great lengths to illustrate, is remarkable in both its range and scope, coinciding with a number of beats that mainstream outlets rarely associate with the art form including mental health, the news media, gun violence, and the LGBTQ+ experience.

The Dot and Line died on May 1 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York, the same Brooklyn neighborhood in which it was born on February 17, 2016, when it published its first story, “Anatomy of an Animated Badass.” The cause of death was exhaustion, pennilessness, and a mutual understanding among the members of its editorial team that it was time to pursue other projects while continuing to advocate for animation in particular, and art in general, in other forms, forums, and fashions.

The Dot and Line’s final act was the publication of an editorial epitaph, That’s All Folks! Its last words were, reportedly, “Ain’t I a stinker?“

Eds. note: This memorial borrows shamelessly and imperfectly, but with much love, from Margalit Fox‘s masterful obituary “John Fairfax, Who Rowed Across Oceans, Dies at 74.” We bow down to the GOAT.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we’ve written about animation of all kinds for more than four years. We’ll miss you! If you’ll miss us too, show us some love on Twitter and show our writers the money on GoFundMe. Read our goodbyes here: That’s All, Folks!