Immediately prior to the U.S. premiere of respected anime director Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai, Hosoda himself explained to the audience at October’s Anime Is Film Festival in Los Angeles that this is a film where nothing really happens. He encouraged everyone to reflect on their own family when watching this film and to focus on the small moments.

While this framing is integral to the film, it undercuts the story that the auteur has crafted. It’s true the film is less action-heavy than some of Hosoda’s previous work (Summer Wars, The Boy and the Beast), but the film’s singular focus creates a profound meditation on the responsibility that family demands and the little decisions that make up the tapestry of life.

Mirai follows Kun, an imaginative stubborn 4-year-old whose parents have just given birth to his sister, Mirai. As Kun struggles to adjust to losing the cute kid spotlight, he finds ways to entertain himself every day in their sloped seven-story house (expertly designed by real-life architect Makoto Tanijiri). He embarks on various adventures with his seemingly imaginary friends, Yukkio, the human embodiment of the family dog, and a teenage version of his little sister, aptly named Mirai-From-the-Future.

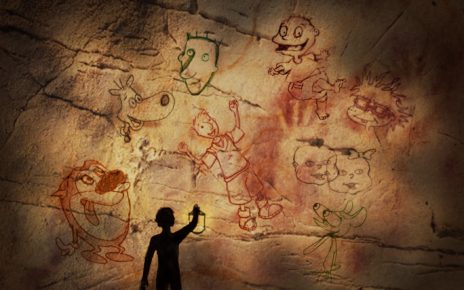

Kun’s adventures beautifully flow between locales, hopping within a single shot from his minimalist garden to his teeming imaginary world. It’s only after a few of these transitions when it becomes clear that not all is as imaginary as we think. Kun’s adventures evolve from hijinks with Yukkio to quaint-yet-powerful vignettes with his ancestors. In a sweet style reminiscent of A Christmas Carol and It’s a Wonderful Life, he starts understanding how important his role as an older brother truly is.

Much of Hosoda’s past work relies on complex plotting; there’s usually a singular and well-defined concept that plays out in the film’s world, and there is almost always a twist. Mirai breaks from this pattern. The rules of Kun’s world-switching are never laid out—in fact, they’re arguably downright inconsistent. The characters hide no twists or secrets, and the viewer is never granted an explanation as to the mechanics of the plot.

Instead, the joy comes from the intense characters Hosoda has created. At the beginning of the film, the viewer is introduced to Kun’s sense of curiosity and wonder as he marvels at his first snowfall. In the same scene, Kun can marvel at baby Mirai as an example of the miracle of life, then can burst into tears, claiming to hate everyone in his family. The narrative confusion begins to feel appropriate as the viewer adjusts to the perspective of the toddler protagonist; he’s confused by much of what he experiences, but his feelings are real nonetheless.

While such a youthful character is, indeed, refreshing, it’s Kun’s parents that feel the most profound. In a reversal of traditional gender roles (much more believably but not unlike those in this summer’s Incredibles 2), Kun’s father stays at home to watch him, while his mother returns to work. A particularly powerful montage in this film shows Kun’s father growing exhausted as he takes on various household chores, works from home, and watches the two kids. Kun’s mother points out missteps in the housework, telling him it’s not enough to take on the housework if it’s not done well. It’s details like this—the laying out of the actual mental load that raising kids brings—where the real relationship of these characters is the most resonant. Their love, patience, and frustration is strikingly real.

In Kun’s beautifully animated adventures with his ancestors, Mirai hammers home the powerful small moments that make this film. There’s such meticulous intention and precision in these scenes both in plot and visuals, specifically in how they lend themselves to Kun’s development as a brother. A standout example of this is Kun’s motorcycle ride with his great grandfather, in which the ride and surrounding World War II-age industrial development is a fluid combination of 2D and CG animation, juxtaposed with gorgeous painterly landscapes. These moments build and crescendo in a climactic sequence that keeps the visual majesty and delivers a tearjerking emotional resolution (this reviewer did, in actuality, shed a tear at what might be the most romantic scene of the year).

Mirai is far from perfect. Its inconsistent and ruleless world will be alienating to some viewers, and at the end of the day, its message is a simple and fairly understood one. That said, it shouldn’t be defined as a film where nothing happens, but rather—if approached with an open mind and childish sense of wonder—one in filled with growth and change even in the most mundane of moments.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to for this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.