Yesterday was Holy Thursday on the Christian liturgical calendar, one of the holiest days of the year, on which Jesus of Nazareth broke bread and drank wine with his disciples and, in Christian tradition, changed them into his own body and blood. It was also the night he was captured before he was sentenced to death by crucifixion, on Good Friday, which is today. It was also the day President Donald J. Trump, a member of the “moral majority”–touting, conservative Christian–representing Republican Party, approved the use of the largest non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. arsenal to bomb Afghanistan—a country in the Middle East just a few nations away from Jerusalem where, at 3:00 p.m. today around 2,000 years ago, that pacifistic holy man breathed his last while nailed to a cross.

Considering all this, this Easter seems like a good moment to address the plight of the American Christian, a label that seems more oxymoronic by the day. It’s time we talked about what is quite possibly the most depressing animated show of all time: Moral Orel.

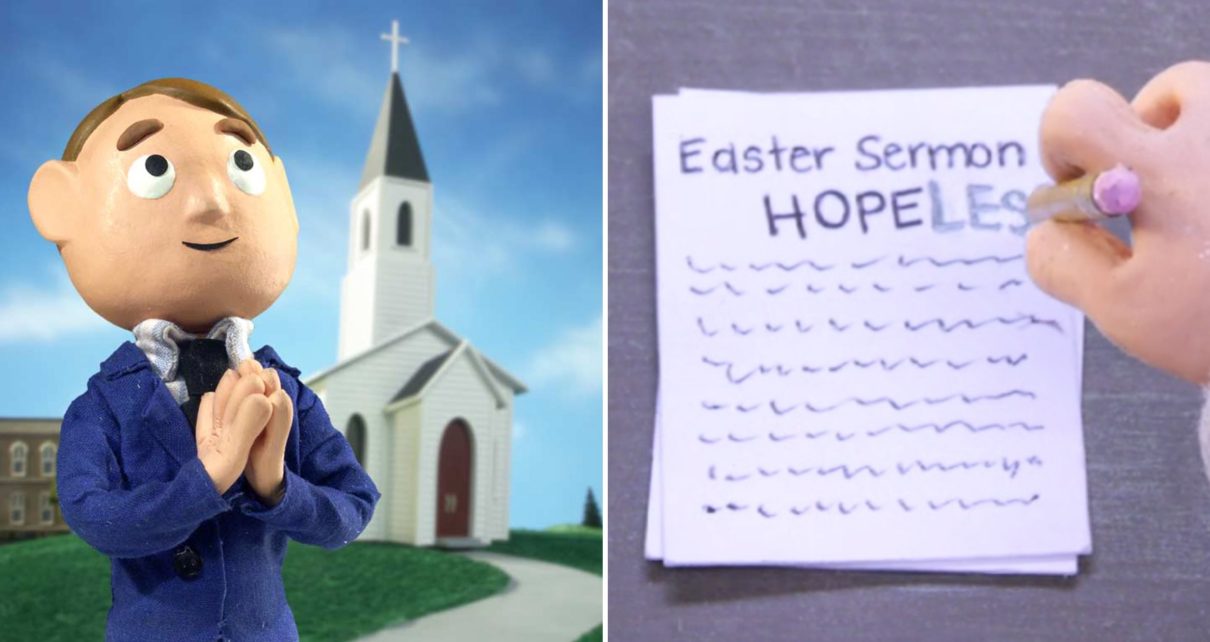

Moral Orel is one of Adult Swim’s strangest offerings. The show was created by talk show and Mr. Show veteran Dino Stamatopoulos, who would go on to help produce and act in Community, and featured a clay-animated stop-motion style. Orel is often described as a parody of the 1960s propagandistic Lutheran claymation show Davey and Goliath, although Stamatopoulos consistently labors to clarify that any similarities are accidental, and that the show’s true inspiration was Leave It to Beaver. Both exist in its DNA, but neither come close to touching Orel’s biting social commentary or its deep inner darkness.

Orel Puppington is a 12-year-old boy living in the fictional state of Statesota in its fictional capital of Moralton. Moralton is a caricature of a small town in the Bible Belt—overwhelmingly white, prescriptively Protestant, outwardly ethical and inwardly teeming with the damage and derangement that comes from years of repressing every emotion and desire in the name of holiness. And Orel is the holiest of them all. An innocent, sweet, cheerful boy who hangs on each word in every sermon delivered by Reverend Rod Putty, Orel calls Jesus his best friend and wakes every Sunday wide-eyed and ready for church—which he has, on occasion, been known to affectionately call “Churchy.”

Orel is, paradoxically, the black sheep in his family. His father, Clay, is an alcoholic who hates his “stinkin’ dead-end job,” ignores his family, emotionally cheats on his wife with Orel’s track coach, and beats Orel with a belt every time Orel does anything he doesn’t like. Orel’s mother, Bloberta, is a disaffected wreck, feigning cheerfulness while also neglecting and emotionally abusing her family and compulsively cleaning to hide her pain and take out her anger. Orel’s brother, Shapey, is a spoiled and emotionally stunted brat who screams all the time; he is Bloberta’s illegitimate child with—no kidding—Orel’s track coach.

Orel is the black sheep precisely because he is exactly what Moralton professes to want its citizens to be. He is generous and kind. He is honest and hard-working. He listens, to a fault, to his elders. It just so happens that those elders give him a bunch of half-assed advice to shut him up and to cover for their own moral failures, and when he follows through on that advice, disaster often occurs, for which Orel is blamed and abused.

If this is starting to sound like an all-too-familiar metaphor, it should.

There’s been much ballyhoo about the white working class since Trump ascended to the presidency on the backs of outraged conservatives, to the point where there is now much ballyhoo about the ballyhoo, and never mind that there’s plenty of data to dispute the whole “the white poor voted the white billionaire in” narrative. And the idea that “most Christians vote for Republicans,” too, is pretty ridiculous, especially when considering that 46.5% of the country, as of last census, identified as Protestant, and around 70% as a Christian of some denomination. Yet the Republican party has painted itself as the party of religious superiority since the rise of the Christian Right in the 1970s, and, recently, as the only party that defends the white working class.

Both are bald-faced lies, and political junkies know it. The conservative movement in the United States has tied traditionalism to neoliberalism and spewed rhetoric of “cultural and fiscal conservatism” when none of the numbers add up. The military—completely contrary to a Christian, i.e. pacifist, way of life—gets all the dollars in the budget while social services are robbed and the poor are left without support.

Yes, the poor. A word you’ll never hear a politician say, but which Jesus said, according to all the gospels—even the Gnostic ones!—all the time. Jesus, who acted as a pacifist social worker and public health advocate, would never have supported gutting Meals on Wheels and funding more foreign wars, and he wouldn’t want women to see their publicly-subsidized healthcare axed because of the misrepresentation of abortion, and he wouldn’t want people dying in mass shootings because it’s so easy to get guns in this country. It doesn’t matter. Those who claim to be holiest reap the lobbyist money and laugh all the way to the bank, steamrolling their constituents in the process.

If “love thy neighbor as thyself” is the greatest of the commandments, it’s been shattered consistently by those who claim to uphold it. This was Orel’s world in a stop-motion cartoon, and we’re living in it.

“The mind is a scary, scary, scary thing! Because somewhere, way down deep inside, in its twisted catacombs and dank, dark hallways, there’s an even scarier, more horribly monstrous entity: truth.”

We already know that Donald Trump didn’t say these words, because Donald Trump doesn’t have the vocabulary, but the sentiment, certainly, is similar. They even come from the mouth of a sociopathic politician toward the climax of Moral Orel. This is, in a sense, the Christian Right’s thesis, and Moralton’s as well. And Stamatopoulos knew exactly how to hammer home that the act of burying the truth—about one’s feelings and needs, about society, about human nature itself—could only result in pain for all involved.

Orel’s third season—in conjunction with “Nature,” the two-part finale to season two—is a grim masterpiece. “Nature” takes place during a hunting trip (hello, Second Amendment!) that Orel takes with Clay, during which he finally recognizes his father for who he really is. The entire third season takes place just before, during, and immediately after that trip, and showcases the secondary characters of Moralton and their minor tragedies: the ignored housewife who resorts to self-mutilative masturbation to gain the attention of the sadistic town doctor; the traumatized schoolteacher attempting a home abortion; the beautiful school nurse, home after a day of sexual abuse at the hands of the principal, speaking to her teddy bears as if they were her husband and children; the lonely Reverend misleading his own flock in an attempt to find love.

Toward the end, once Orel’s eyes finally begin to open to the hypocrisy around him, Stamatopoulos allows his guarded, broken community to admit to itself what it is. And in what must be the most bilious, piteous soliloquy ever made by a claymation character, Clay Puppington—the incarnation of a community’s failings, voiced by a young and utterly marvelous Scott Adsit—finally tells it like it is.

If only it mattered.

Moral Orel ends on something of a high note, and it’s sort of hard to believe even after you watch it. This is, after all, a show that opened its third season to the Mountain Goats’ “No Children.” But that note is a lonely one, sounded only by the one character the failures of American conservative Christianity could not break: Orel himself.

Because Orel, finally, realized something that the white Christian working class in this country—so long exploited by a broken system, so long taken advantage of by a party that purports to protect their rights even as it robs them of their voices, their basic human needs, their rights—has not: the truth is not just an inconvenience, but a principle. And in order to get past the horrors hidden by lies, you need to accept them for what they are.

“Not saying what’s on our mind is what this country’s based on,” Clay Puppington tells Orel near the end of the series.

Maybe it’s time we fixed that.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to ❤ this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.