This post contains spoilers for BoJack Horseman Season 4. The information provided in this article is for entertainment and educational purposes only, and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, mental health professional, or other qualified health provider with any questions or concerns you may have regarding a medical condition.

Every horse thinks his own pack’s the heaviest, but BoJack Horseman will tell you he’s always had to carry his 15 miles uphill both ways through a California earthquake. He’ll also tell you that his drinking and drug use is the most destructive, and that his eating binges are the most out of control; that he is the worst possible friend, partner, and son; and that he is the ugliest, meanest, most self-loathing horseperson around. But BoJack’s suffering exists largely in a spacious, well-decorated vacuum. Sure, his parents were neglectful and abusive, but why does his pain persist? He has all of the fame, fortune, and flings he could ever ask for—and then some.

What BoJack doesn’t know is that his predisposition for impulsive behavior, unstable relationships, and self-hatred was brewing well before he was born. In fact, BoJack’s particular brand of sad has deep, gnarly roots, and they are tangled inextricably from those of his family tree.

The ways in which parents fuck up their children has been more than well established by psychology theorists, researchers, and practitioners. Freud’s Oedipus/Elektra complex, Winnicott’s good enough mother, Bowlby and Ainsworth’s attachment theory, and many others have explored how the caregiver-child relationship sets the stage for a child’s behaviors, personality, approach to relationships, and understanding of herself and the world around her. Much of the communication in these relationships is non-verbal; a mother can tell her child over and over that he is safe, but her anxious facial expression will be what he registers.

This kind of implicit communication, however, isn’t just found between immediate caregivers and their children. It has an uncanny way of stretching back generations—often with the specifics of, and contexts surrounding, these conversations blurred and forgotten over the years. Time’s arrow, after all, marches forward.

Unfortunately for BoJack, he cannot march forward without understanding how the trauma his grandparents and parents experienced has seeped it’s way into his subconscious. That’s where an idea known as intergenerational trauma comes into play in Season 4 of BoJack Horseman.

The psychologists and psychiatrists who have developed the various iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) have established that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops in response to both directly experiencing a traumatic event (e.g., being sexually assaulted), or to indirectly learning about it (e.g., finding out that your best friend was murdered). But these researchers, thinkers, and clinicians, esteemed as they are, have made the choice not to include the full, multifaceted picture of how trauma and our responses to it manifest and operate.

PTSD is just the tip of the iceberg (no, not that iceberg) as far as the number of ways that people feel, think, and behave in response to experiencing trauma. While the DSM does account for diagnostic comorbidity—that is, which mental health diagnoses people tend to be laden with at the same time—it remains both categorical and largely non-etiological. In other words, it conceptualizes the various mental illnesses (e.g., depression, binge eating disorder, schizophrenia, etc.) as their own distinct categories and only lightly touches upon the factors that cause them.

Years of research and clinical theory and experience have suggested that a wide variety of mental illnesses can develop in reaction to experiencing trauma. Many of these disorders—including but not limited to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders, substance use disorders, and borderline personality disorder—are useful but maladaptive ways of numbing extreme psychic pain. And BoJack is the perfect clinical example of a person trying to keep his traumatically-induced pain at bay, manifesting symptoms of several of the aforementioned mental illnesses. He drinks and uses drugs to excess and then some. He eats compulsively while hating his body and berating himself for binging. He struggles to maintain stable relationships, alternately idealizing and despising his friends and partners.

Although behavioral therapy and psychiatric treatment could help BoJack decrease the frequency with which he engages in these kinds of self-harm, it wouldn’t address the root of the issue. This kind of treatment unintentionally segregates the person’s behaviors from his thoughts and feelings about his traumatic experience. And, ironically, this symptom-reduction treatment actually re-enacts the insidious ways in which trauma affects us rather than mitigating its poison.

As psychoanalytic psychiatrist Richard Chefetz argues, trauma fractures what would otherwise be integrated aspects of our consciousness. Our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors typically co-exist, working together to ensure that we think, feel, and act appropriately in response to any given situation. Trauma shatters this harmonious cooperation. Disturbing memories hold little emotional weight; behaviors continue in the absence of a reason; emotions are disconnected from thought—some wild and easily provoked, others stunted and eerily silent.

With directly experienced trauma, people can more easily knit together their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors: understanding how their misplaced emotions and behaviors connect with their traumatic experiences.

But what happens when people don’t know about the traumas they’ve experienced? We’re not talking here about the ever-controversial repressed memories theory. We’re talking, rather, about how trauma is both forgotten and passed on from generation to generation. We’re talking about intergenerational trauma.

Season 4 of BoJack explores the intergenerational transmission of trauma, and this exploration provides its eponymous character with glue he can use to start to piecing the fractured pieces of his consciousness back together. (Horse glue pun not intended.)

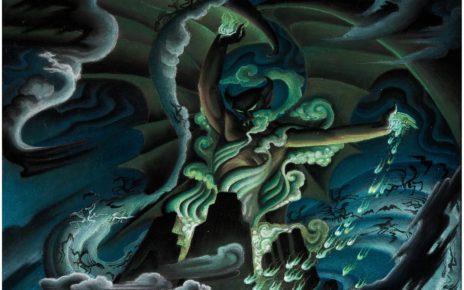

In it, we learn that BoJack comes from a long line of broken-hearted horses, starting with his grandmother, Honey Sugarman, expertly played by the theatrical goddess Jane Krakowski. After her son Crackerjack—voiced by Broadway’s sweetheart, Lin-Manuel Miranda—is killed fighting in WWII, Honey’s intense and prolonged grief causes her psyche to unravel, culminating in an inebriated, public breakdown during which she tasks her young child, BoJack’s mother Beatrice, to drive them home.

The incident ends in emotional turmoil, with Honey begging her husband Joseph to “fix her.” In this case—this being the 1940s, after all—the “fix” involves crudely butchering her pre-frontal cortex. The young Beatrice was there to bear witness to her mother’s breakdown, and forced to pick up the pieces of her broken family. And years later, Beatrice, through no fault of her own, becomes a conduit for that entrenched familial pain. (She says as much in Season 2.)

Trauma, whether it’s intergenerationally transmitted or directly experienced, can hijack our brains and unconsciously motivate us to create and re-create the traumatic events we’ve experienced. Freud aptly named this the repetition compulsion, arguing that we bring the past into the present as a way of developing mastery and skill in a situation that once caused us great pain and harm.

BoJack’s family trauma seems largely centered on the relationship between parent and child, with each of his family members attempting to find some semblance of control and stability in a tumultuous parent-child dyad. Honey had her beloved son ripped away from her in the war, while Beatrice’s father coldly ripped her beloved baby doll away from her, burning it in their fireplace while ignoring his daughter’s pleas to keep her doll alive. Later, Beatrice coerced her maid Henrietta into giving her baby up for adoption and, much like her father did with her doll, whisked away the infant horse before Henrietta even got the chance to hold her. Later, in some of the most subtly tragic scenes in the season, Beatrice — who is showing signs of age-related dementia — gently and lovingly parents a baby horse doll that looks uncannily like the one her father destroyed many years before. BoJack ironically interrupts his mother’s attempt at repairing her trauma; like his mother and grandfather before him, BoJack rips “Doll” away from his mother, and throws her out of his window in a fit of jealousy and rage.

BoJack also re-creates this kind of cold and neglectful parent-child relationship with Hollyhock, pushing her away every time she attempts to establish a healthy connection and level of intimacy. In this case, however, BoJack’s repetition of his mother and grandmother’s failures seems to break the cycle of abandonment. When Hollyhock’s fathers cut off contact between the two horsepeople, BoJack does everything in his power to give Hollyhock closure about finding her birth mother. And, uncharacteristically, he does it selflessly, relinquishing credit for discovering that Hollyhock is actually BoJack’s sister—the same child that Beatrice forcibly put up for adoption.

Does this mean that BoJack is cured of his disordered eating, substance abuse, and interpersonal lability? Not even close—a trauma so entrenched can’t be dug out so easily, if ever. But BoJack has noticeably softened by the end of the season. He’s starting to let himself be vulnerable and empathetic, understanding that relationships have just as much potential to heal as they do to hurt. Perhaps his new found ability to relate to others will allow BoJack to finally feel something on the inside and something on the outside.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to ❤ this article and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.