You’ve heard of Looney Tunes and, one would hope, its sister, Merrie Melodies. But despite the long-lived popularity of Warner Bros.’ most beloved cartoon shorts series, the Walt Disney Company actually beat them to the punch with its own: Silly Symphony.

Typically, calling something a “passion project of Walt Disney’s” doesn’t do much to recommend it, what with the animator-turned-entrepreneur’s penchant for patriarchal, sexist, occasionally racist, and quintessentially pro-capitalist messages in his work, not to mention union busting. (Wait, please, don’t close this tab yet!) Yet when the Silly Symphony series debuted its first short, “The Skeleton Dance,” on August 22, 1929, relatively hot on the heels of the first Mickey Mouse cartoon, “Steamboat Willie,” which premiered on November 18 of the prior year, it changed the history of animation forever. And in a good way.

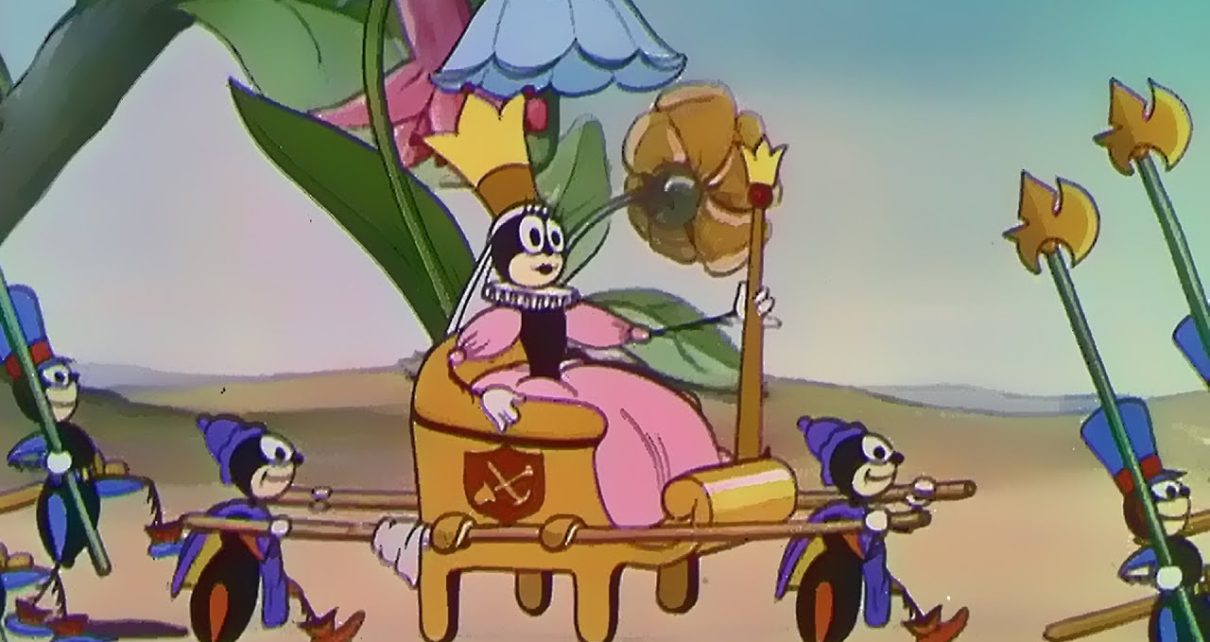

It’s hard to overstate the impact, however overlooked it is today, Silly Symphony had on American animation. The series, which would eventually comprise 75 short films, had three primary characteristics: 1. whimsy; 2. song and dance; and 3. one-off characters. Only three Silly Symphony films—Three Little Pigs, The Tortoise and the Hare, and Three Orphan Kittens—ever saw their protagonists return in consequent Disney installments, with the exception of Donald Duck, who was, believe it or not, introduced in one of these shorts.

As a result, Silly Symphony proved a hotbed of innovation, eventually leading Disney to experiment with Technicolor and the multiplane camera. It also won the Walt Disney Company seven Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film, leaving the series tied, with Bill Hanna and Joe Barbara’s Tom and Jerry, for the all-time record in that award. And, seeing as this was the Walt Disney Company, it also birthed merchandise: spinoff newspaper comics, comic books, and children’s books all resulted from the shorts’ successes.

Remarkably, many of the shorts still feel fresh, in part because they were so innovative. “The Skeleton Dance” remains a classic, and highly recommended for Halloween parties. In “Hell’s Bells,” legendary Disney collaborator Ub Iwerks brings viewers on a bizarre trip through hellfire just a few months later. “Flowers and Trees,” from 1932, was the first Technicolor cartoon, and the first cartoon short to win an Oscar. Its follow-up, “Santa’s Workshop,” was the first cartoon to employ optical sound. “The Old Mill” was Disney’s multiplane camera debut, and laid plenty of groundwork for Dot and Line staff favorite Over the Garden Wall. “The Three Little Pigs,” from 1933, also won an Oscar, and inspired Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

The series wrapped up in 1939, two years after the release of Snow White and two before Bambi hit theaters, and the later shorts were less experimental, less memorable, and proved Disney had shifted his priorities elsewhere. (It also wasn’t a consistent moneymaker, despite the occasional hit.) But in today’s world—a world in which the sexism of many of Disney’s biggest properties is finally getting its share of criticism while the company continues to milk those properties for everything they’re worth in mediocre (at best) reboots—it’s nice to be reminded of what brilliance the animators at the Walt Disney Company can bring to the table when the relentless pursuit of capital isn’t at the center of the equation.

Thanks for reading The Dot and Line, where we talk about animation of all kinds. Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and sign up for our newsletter.